Ep. 398 Writing Palestine Alive with Sarah Aziza

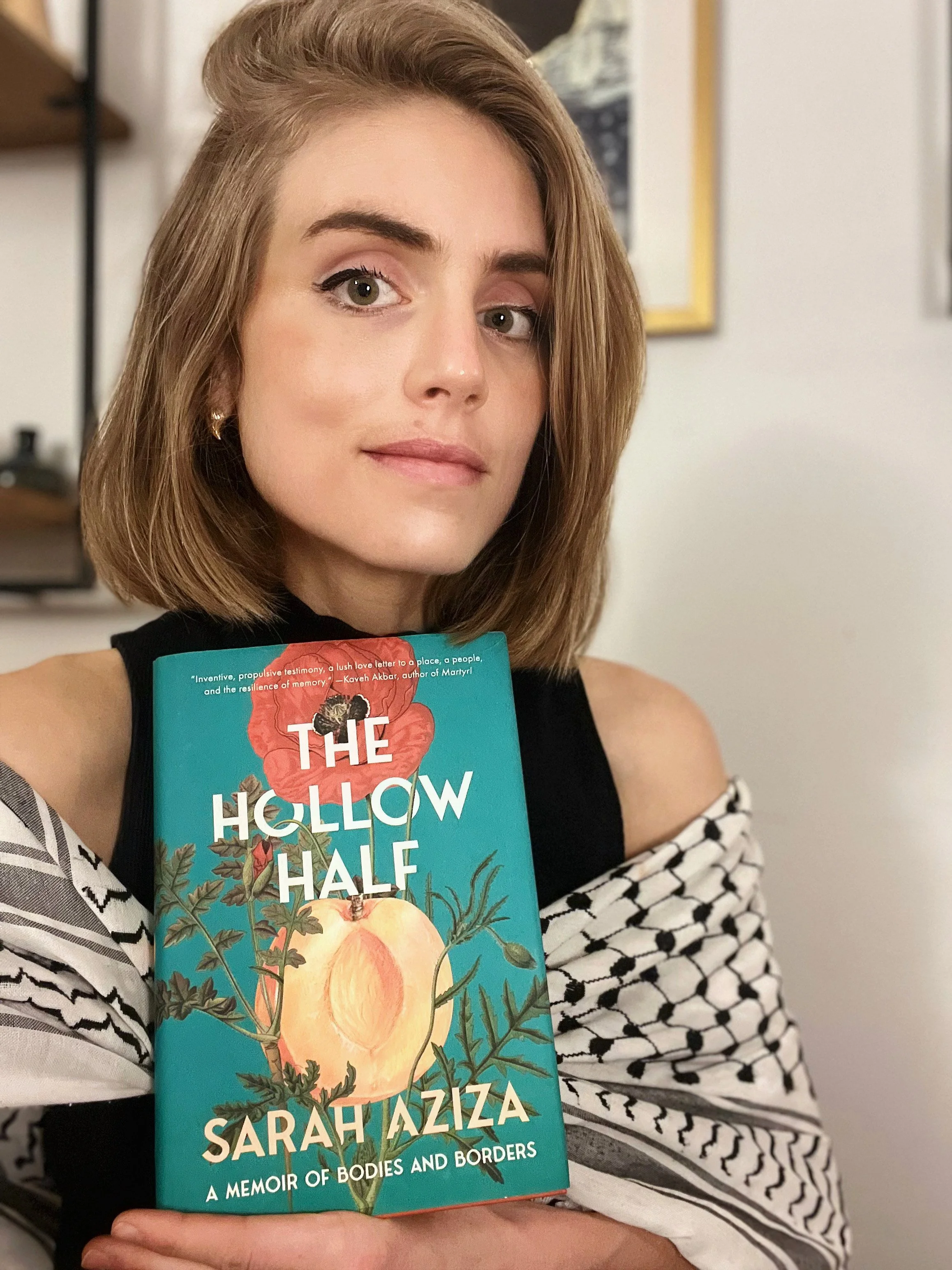

Today on The Stacks, we are joined by Sarah Aziza to talk about her debut book, The Hollow Half: A Memoir of Bodies and Borders. In this memoir, Sarah explores her struggle with anorexia through the lens of her family’s history of violent displacement from Gaza, drawing haunting parallels between her personal and ancestral trauma. We talk about why she wanted to trace these connections, how she uses footnotes to complicate the narrative, and how she sees her work in conversation with those of Black feminist scholars.

The Stacks Book Club pick for November is We the Animals by Justin Torres. We will discuss the book on Wednesday, November 26th, with Mikey Friedman.

LISTEN NOW

Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Google Podcasts | Overcast | Stitcher | Transcript

Everything we talk about on today’s episode can be found below in the show notes and on Bookshop.org and Amazon.

The Hollow Half by Sarah Aziza

The Hollow Half by Sarah Aziza (audiobook)

“Venus in Two Acts” (Sadiya Hartman, Duke University Press)

In the Wake by Christina Sharpe

Heavy by Kiese Laymon

Frankenstein by Mary Shelley

“Ep. 396 Frankenstein by Mary Shelley — The Stacks Book Club (Angela Flournoy)” (The Stacks)

To support The Stacks and find out more from this week’s sponsors, click here.

Connect with Sarah: Instagram | Threads | Website

Connect with The Stacks: Instagram | Threads | Shop | Patreon | Goodreads | Substack | Youtube | Subscribe

To contribute to The Stacks, join The Stacks Pack, and get exclusive perks, check out our Patreon page. If you prefer to support the show with a one time contribution go to paypal.me/thestackspod.

The Stacks participates in affiliate programs. We receive a small commission when products are purchased through links on this website.

TRANSCRIPT

*Due to the nature of podcast advertising, these timestamps are not 100% accurate and will vary.

Sarah Aziza 0:00

I needed to reorient myself and the way I understood the world and my and and and my body and things like that. And, you know, I had to build this whole map, right, this web of, you know, over 100 you know, different thinkers and writers, you know, and like, years of therapy and listening to my body and all of these, like somatic things, I'm like, I wish I had been given any of these tools or any of these frameworks or a different way to think about myself or my body, so I really wanted to share as much of that as a resource just to be out in the world. It's just like one more place that somebody might stumble upon and, like, learn a little bit like, maybe, you know, take some, you know, solace and comfort, or, like, wisdom, you know, without having to earn it the way I kind of paid for it.

Traci Thomas 0:49

Welcome to The Stacks, a podcast about books and the people who read them. I'm your host, Traci Thomas, and today I am joined by author Sarah Aziza to discuss her debut memoir, The Hollow Half: A Memoir of Bodies and Borders. This book traces the haunting parallels between Sarah's struggles with anorexia and trauma and her Palestinian family's history of displacement and erasure. And on this episode today, Sarah and I talk about why she left writing, what made her come back to it, and how she has felt about taking this book out into the world. As a reminder, our book club pick for November is We the Animals by Justin Torres, we will discuss the book on Wednesday, November 26 with Mikey Friedman. Everything we talk about on each episode of The Stacks is linked in our show notes. And if you like this podcast, you want more bookish content and community, consider joining The Stacks Pack on Patreon and subscribing to my newsletter Unstacked on Substack, each place offers different perks, like community conversations and virtual book clubs on Patreon, and my writing and hot takes on the latest literary and pop culture news on Substack, plus in both places, you're going to get monthly bonus episodes, and joining makes it possible for me to make this podcast free to all every single week. So head to patreon.com/thestacks to join The Stacks Pack and check out my newsletter at TraciThomas.substack.com All right, now it is time for my conversation with Sarah Aziza.

Right, everybody, I am thrilled today I am joined by Sarah Aziza, who is the author of The Hollow Half, which is, as you all know, I have been reading a lot of memoirs this year that I have hated, and this was one of the first memoirs I have read since May that I was like, this book is amazing. So I am thrilled, thrilled, thrilled to welcome Sarah to The Stacks.

Speaker 1 2:36

Thank you so much. I'm glad to hear I broke that streak.

Traci Thomas 2:39

You did, because I had, I had gotten to the mindset where I was like, maybe the genre of memoir is done. Like, maybe we've memoired enough. We have out-memoired. Maybe, maybe things die, things change. Like, maybe we have done it too much. And then I read your book and I said, Well, some people can still write memoirs.

Sarah Aziza 3:04

Well, I'm touched and honored. Thank you.

Traci Thomas 3:07

So for people who don't know, will you just in like 30 seconds or so tell us about The Hollow Half?

Speaker 1 3:13

Sure, so it's, it is a memoir, I guess, technically, but I do kind of like braid in a couple of different genres. There's oral history and archive and dream work and speculative nonfiction, I like to say, but the general like subject matter that it covers is three generations of my family from British mandate Palestine through 1948 the Nakba, becoming refugees, first in Gaza and then, after '67 dispersed into Saudi Arabia, and then eventually, in my timeline, New York City, and just about exploring themes of mental health, diaspora, yeah, and just like the recovery and healing of, like intergenerational love, I guess, to just go real big,

Traci Thomas 3:59

yeah, okay, I want to come back to all of that, but I've never heard the term speculative nonfiction. Yeah, please say more.

Speaker 1 4:07

Sure, I think I probably picked it up somewhere, or maybe it was just, you know, learning more about speculative fiction. But I sort of reached for that term. I think it was like maybe a residency application I was writing early on in the process, when I was trying to sort of capture what I was doing, which is, it's drawn, in some parts from Sadiya Hartman, who's a scholar who has this idea of critical fabulation. So this idea of, like, you spend a lot of time in research and the archives and other forms of like nonfiction reportage, but then there are moments of like imaginative leaps, or in some instances, because the book is also forward looking, just imagining towards sort of like meanings that cannot necessarily be factually, you know, codified or proven, but are sort of like. Based around, like, the collaboration of, like, ancestral work, imagination and research.

Traci Thomas 5:04

I love this I love this term. I'm like, my brain is going on trying to think of, like, other books that maybe are sort of that also maybe are speculative non fiction. But I feel like I'm drawing a blank, though. I'm sure there are things I have read I'm just processing as you're talking.

Speaker 1 5:19

Yeah no, it's Yeah. Genre is always like a fiction in itself. But I like that term.

Traci Thomas 5:24

I do like that term. I feel like for what you've done, you know, I have a term though I don't, I don't know, maybe your book is this. I have a term that I like to use where I just call it memoir plus, which is like, it's memoir plus research, plus other things. Though, I don't have a clear enough definition in my head of what memoir plus is, and I don't know that yours is. I feel like the word braiding that you used is much more accurate. Like this is definitely like a braided memoir, because you're pulling on these different times and these different strands, and then also you're pulling on your own, like sort of mental health and physical journey, because the book sort of kicks off with you going into treatment for anorexia and so and that sort of is, at least the way that I read it was sort of what, what prompted you to kind of go on this historical family journey. So could you talk about how those like, how your treatment led you to kind of look backwards into your family history?

Sarah Aziza 6:20

Sure, so the book does open on, actually, October 2019, entering into inpatient treatment for severe anorexia. And I sort of arrived at that point, like in my mid 20s of, like, just basically almost at the point of death, to be totally honest. Like very medically, physically compromised, but also in this state of, like, being so estranged from myself, as far as, like, my mental and emotional state, and really, sort of, like the shock of realizing the point, the low point that I had reached, and the way that that kind of conflicted with the story of self that I'd had of, you know, I am a third generation removed from, like, the Nakba, the disaster of, like, our ancestral lands being ethnically cleansed. And, you know, my father was born in Gaza without shoes until he was six years old. All of those, you know, like the lore a lot of immigrant kids have of like, you're the lucky one, the privileged one. So how did I end up basically imploding in this way? Was like, a question I really had no answer for at the time, and then I was confronted with this western model of mental health, which is just like, very individualistic, like, let's focus on you, what happened to you in the last 20x years, and that's where we'll find the answer, and we'll fix you. And just like, that model just really not holding what I was holding. And then into that comes a lot of memory that starts to jog this like idea, the seed of like this, this must be about more than just me.

Traci Thomas 7:49

When did this become a book to you? When did your treatment and sort of looking back into your family and making these connections become something that you knew needed to be on the page versus just part of your process of life?

Sarah Aziza 8:02

Yeah, actually, it was a really long time coming to admit that I actually, before I was hospitalized, I was a journalist. I have a master's in journalism, so I was writing in sort of like a somewhat public way. I was, you know, young getting started out, but I really left the hospital. I was there for four months, and it was a very carceral sort of experience, and very demoralizing, and I left very humiliated. I don't think that was the point. Like they didn't mean to do that, but they didn't work really hard to keep us from feeling humiliated. It was very punitive. So I basically swore, among other things, that I would never write again because I just, I had internalized this idea of, like, your mind's broken, you're crazy. And so doing anything public facing was completely mortifying to me. So I ended up, you know, the writing started sort of in this and, you know, you might hear me, you use a few kind of, like woo words in this conversation.

Traci Thomas 9:01

I live in LA, it's fine, I'm familiar with woo words.

Sarah Aziza 9:05

Okay, amazing.

Traci Thomas 9:06

Safe space.

Sarah Aziza 9:09

Thank you. So I started having these dreams that I don't even know if they were exactly dreams, but I was waking up. I allude to them a little bit in the book, but waking up with sort of the sense of my grandmother being in the room, and she, at that point, had been dead several years, and I was sort of without even fully waking up, finding myself actually at my partner's desk because I had gotten rid of my desk, because I had quit writing. But I was at my partner's desk writing, sort of in this dream trance like state where, you know, out of nowhere, I was just trying to record these childhood memories that were coming back to me, and they were very visceral, physical memories. And then from there, you know, the pages just started adding up. And then I got curious, because there were so many gaps in what I could remember, and so many questions that were coming up about my grandmother's life. And so I started, you know, asking my father questions. And then start. Started to, like, tiptoe into just research. This was also like, 2020, so pandemic times. I was, like, secluded in this weird, like dream slash, like bookish research hole. And it was a dear friend of mine that, you know, eventually confronted me, like gently was saying, you know, I think you're writing a book. And that was when, you know, it struck me so to my core, like it was the split second difference between this recognition, this leap of recognition in my chest, and then this fear that came right after it to sort of clamp down on that. I'm like, No, I could never do that. I'm not a writer. So then it was a negotiation between those two forces for a while, but eventually, yeah, she was right. The writer came back.

Traci Thomas 10:41

Okay, let me ask you this, when you quit writing, you were like, I'm not a writer. Can't do it. Something's wrong with me. What were you professionally? Did you take other jobs? Were you just sort of just trying to survive? What was that interim period when you, like, weren't a writer?

Sarah Aziza 10:59

Yeah. I mean, I got discharged in February 2020

Traci Thomas 11:06

Tough time to find a job.

Sarah Aziza 11:07

I know, things were shifting a bit. I had filled out a few job applications. I really wanted to work at this wine shop down the street. I thought that could be fun and cool and okay, I could learn about wine and mostly not talk to people. And yeah, just, you know, sort of do odd jobs like that. Then when we were in, you know, remote work life, I just, I did some translation and, like, proofreading in Arabic for, like, some wire services and stuff. So, yeah, I was just stringing things along. And then, you know, by like, 2021, I was, like, back, you know, slowly in the journalism slash writing space.

Traci Thomas 11:44

So you went back to journalism before the book came out.

Sarah Aziza 11:47

Yeah. I mean, I, I wasn't calling myself a journalist, because, for some reason, having that mental separation helped. I was saying I was a writer. So I was getting more into like essays and like analysis. My first essay was about my grandmother, but I used my grandmother to talk about capitalism and relationships to time. But, yeah, no, I was just like, you know, finding different ways for me to, like, trick myself into writing again. So I was, I was doing essays. I wasn't a journalist.

Traci Thomas 12:13

Yeah, totally, I get it. I'm not a writer, even though I write things all the time, but whatever. Yeah, I'm just not a writer. I don't like it, and I don't ever like it, and I don't ever want to be one. I just write. So, like, I have the same kind of thing, which is, which is different. I used to run, and I instantly was like, I'm a runner. Oh, even though, you know, like, you know, like, I have no problem saying, like, things that I do, I am. But for some reason, with the writer. I'm just like, I'm not a writer, I think because I don't want people to judge me in the same way that I judge writers. Because I'm like, Well, I'm not that. Like, I don't care. I know it's bad. I know my writing sucks. So I feel like I understand the sort of like mental like, I'm not a journalist even though I'm doing journalism, or like, I'm not a writer even though I write. It's weird, I get it. Yeah, and people like, get mad at you when they're like, but you are a writer. I'm like, No, I'm not a writer

Sarah Aziza 13:11

I mean, it is your journey. It is your you know, it's like, our pronouns, you know, you get to claim what you feel

Traci Thomas 13:21

You get to decide who you want to be. Totally.

Sarah Aziza 13:21

I wouldn't wish the writer's life on anyone.

Traci Thomas 13:23

Yeah, well, I'm not one, so I don't have that. But it's funny because I'm like, I think it's way more embarrassing to be a podcaster, but I have no problem being like, I'm a podcaster, but it since 2020, has gotten embarrassing.

Sarah Aziza 13:35

Oh, well, your podcast is a good one. We want it.

Traci Thomas 13:39

Well, they just let all these guys have microphones now.

Sarah Aziza 13:41

Oh, I know there should be a different word. It's like, I'm not that.

Traci Thomas 13:46

I'm not Ezra Klein, you guys. I talk about books like I'm not, I'm not a total egomaniac. Okay, so one of the things that your book does that is different and cool, and a few of my other favorite books do this, which is, you use footnotes in a really different way than a traditional footnote. Some of your footnotes are like little essays, or like little you know, like they're little micro informations, and some of them are just, you know, sentences. But I'm wondering how you were thinking about footnotes when you decided the footnotes were necessary, how robust you wanted to make them. Just talk about the footnote situation.

Sarah Aziza 14:32

Thank you. I'm grateful for this question, because it was there was an evolution there. One of the things that I feel like is really important to me as like a person now, but also as a writer, is sort of like undermining this idea of the author as, like this single authority, like voice of authority, and also like just a human being as an individual, you know, enclosed entity, I think that we're all just like very porous. And we're all poured into and like the creations that we make, whether it's podcasts or writing or relationships like are all built from, like the materials that are recycled from what we read or who raised us, or what we've consumed in culture. So I really wanted the story to, the word I use is jostle. I wanted it to not feel like I'm just this declarative voice, constantly speaking with total confidence. So there are some footnotes that complicate or complement what I'm saying in a way that I found was interesting. So, you know, I'm not, you know, I know when you have an identity that is just other than like cis, white male, people might come to your book and think like, this is the Palestinian perspective, or this is the female or the queer. So I wanted there to be lots of Palestinians that people were getting introduced to, just other canons in general. I wanted to also pay homage and sort of honor, like the people who taught me how to think in certain ways. Who, who I'm directly drawing from. So the Sadiya Hartman is one of them, Christina Sharpe, like, there's a lot of, like, black feminist thinkers that really influenced me. So I felt like they needed to be they needed to be visible for it. You know, that was important to me. And so there's a lot of footnotes that are really I ended up putting as endnotes because I wanted them to have, you know, just like their own space. And it was a little messy when I tried putting them all on the pages as footnotes underneath, yeah. So I ended up making this sort of distinction for myself, that the goodies, as I like to think of them, like the jewels, the resources, the good stuff, the stuff that I'm really excited to share with my readers are in the back. So yeah, you can go to the back on your own time, whether in the middle of the reading or at the end, and just like, really spend time with these writers. And they're sort of like, you know, organized by chapter. So there's like, an interesting to me, like conversation that you can read there, and also just, it's just like a little bit of a, you know, if you, if you take the time, you'll be rewarded by going to the back. But then there were other things I didn't want readers to be let off the hook on. For example, a lot of the like political footnotes about this is, like the way in which, like, the US funded, you know, if you see my family getting displaced or killed, there might also be a footnote that's a quote from like, the US president at that time that was boasting about, you know, sending arms to Israel, or, yeah, just like, horrible racist like Supreme Court decisions that were made in like the 1900s about immigrants and who's classified as what race and things like that. Because I wanted, again, like the structural, like complexity and also like responsibility of especially like an English, English speaking/American reader, I wanted them to feel that way, sort of complicating their relationship. So it's not just like this distant, like, Well, that happened to those people and has nothing to do with me, and I'm just, like, voyeuristically looking in, but like, so there are those footnotes that are like, at the bottom of the page. So there's, you have to skip over it, and you have to feel yourself skipping over it if you're not going to, like, take responsibility and read it. So those are some of the things that are happening there.

Traci Thomas 18:16

Yeah, I want to just because I know a lot of my listeners are audiobook people. And I did listen to this book on audio, and I want to just say you do an amazing job narrating. And also, if you are thinking of listening to this book on audio, I suggest you also get a copy, a physical copy from your library or online or whatever, because of the way that it's structured, with the footnotes and the end notes, they don't they're not. Like in the audiobook, you have to listen to all the footnotes at the end. So it makes sense to kind of like bounce in between both forms. I usually feel like, you totally fine doing one or the other. But with this, I'm like, if you're gonna do audio, you also want to do physical in some way, because of how the footnotes function as sort of like, like a confrontation

Sarah Aziza 19:09

Thank you their way of saying it. I appreciate, yeah, it was tricky to figure that part out. It's hard.

Traci Thomas 19:13

It's really hard. And I think, you know, I know, as an audiobook person, and as a person who talks to a lot of people, if the footnotes like were inserted in, it wouldn't work story wise. Like, I understand the choice, but I'm definitely like, if you're gonna listen to get even more out of the book, you also want to to get your eyes on, if possible. You mentioned the black feminist scholars, and that was obviously something that, like, jumped out to me in the reading of the book. And I'm just curious, like, when did their work come to you? When did it come in your career? How did you know that it was going to be important to have these other voices? And it's not just black feminist scholars. There's, I mean, I feel like Vietnam's in here in some of the endnotes. Like you said, many Palestinian voices, but I am interested specifically in the black feminist scholars.

Speaker 1 20:07

Absolutely, well, a lot of those voices had been sort of like in my ear since college. One of my best friends in college. Her name is Elise Mitchell. She's now a professor of Africana Studies, I believe, is like the official title, but she and I feel like, intellectually, we're sort of, like growing, you know, we met our first week as fresh as freshmen, and had a lot of, you know, great conversations about what we were reading and learning, and not just her. But I think, like I was involved in, like, Black Lives Matter activism. That was like my start, and also I majored in comp lit, comparative literature, which involved a little bit of critical theory. So I feel like there's certain names like bell hooks or Audre Lorde that I can't remember, not knowing about. Yeah, and then a little bit more contemporary, I don't know. I don't remember how. I think it was an essay by Carmen Maria Machado that referenced Sadiya Hartman, that opened me up to that essay, Venus in Two Acts, that opened me up to more of Sadiya's work. Christina Sharpe I came across because I think I heard Natalie Diaz, the indigenous poet, scholar, reference In the Wake. And In the Wake ended up being a very like formative book for me. And so you sort of start to build this web. You start to hear people referencing each other, and you stumble. Maybe you're at a physical bookstore, and you see who else is on the shelf or the library. So some of it was very organic. Some of it was seeking out. I had a phone call with Elise, she was working on her first book, which is a scholarly book about the Middle Passage, just as I was writing about the Nakba, so we were really like, going through it. So yeah, her work has a lot to do with, like epidemiology and like the black body. And she's brilliant. So yeah, if you're into any of that, I highly recommend.

Traci Thomas 21:51

Let me ask you then I guess the second part of this question, which is sort of, how do you see yourself and your work in this lineage?

Sarah Aziza 22:00

Very, very like, grateful, wide eyed, like little sister. Like, I definitely don't put myself in league with these people, necessarily, but, yeah, I just think I see myself as in conversation. I see myself as like, wanting to always like own that you know, I'm an American citizen or a US citizen, often white passing in most spaces. And yeah, just have privileges that put me in. Yeah, I'm not always like, you know, Viet Than Nguyen talks about this too. Like, when does the refugee become the settler? Like, I'm in this complicated space of just like, the intersection of, in some ways, Palestinians are some of the most demonized people right now. Muslims are also, you know, in this really vulnerable, demonized place. But I also benefit from, like, systematic oppression that is built on. You know, centuries before my people were dispossessed, there was a genocide here. You know, there is like, just this, like historic and ongoing, like, exploitation and violence of black bodies. And so I want my, yeah, I want my responsibility to be owned as much as my, like, family's like victimization and our struggle for liberation that's incomplete. And I just think that there's, like, a lot of systems that are really invested in us not recognizing the ways that our oppressions and our privileges are sort of intertwined, and we're meant not to be in solidarity and kinship with each other. So, but I also think that, you know, there needs to be the reckoning of who has been indirectly or directly a part of harming another. So, yeah, just it's a complicated ongoing thing, and I want to keep responsible and keep honest about that.

Traci Thomas 23:42

I feel like the ways in which you brought all these voices together in your book was really powerful for me as someone who, sort of, you know, I'm very type A and so I'm really good at, like, putting things in boxes and in places. And so for me, so many of the voices that you sort of call on and commune with throughout the book are people whose work I've read and maybe have thought about them in their own compartment that fits whatever you know, identity markers you want to put them in. But kind of having these different voices that you've pulled together was really exciting for me. Of like, of course, this is actually the same exact conversation. It's just happening in this country, or happening with people who, you know, look like this, or people who talk like this, or people who believe this, but it really is the same conversation. And I think sometimes when I'm talking to people in my real life about politics, that those connections are easier to make, but sometimes, when I'm reading a book, I do fall into the trap of like, this is a book by a Palestinian American woman, and like, this is about her life in America and her family in Palestine. But it's like, of course, this is also about much bigger things, and it is in conversation with bell hooks, or it is in conversation with, I don't know, whoever you know, Kiese Laymon, right? You call on all of these names. You know, he's crowd fan favorite here. So I think the ways that you did it really did resonate for me. Of like, yes, of course, these things like, all come together. I want to take a break because I want to totally shift topics, or not totally shift, but I want to shift a little bit, so we're going to take a break and then we'll come right back. Okay, we're back. I want to talk about, so the subtitle of your book is a memoir of bodies and borders, and I'm going to be honest with you. My sister in law told me about the book. She was like, I'm reading this book. I love it. You should check it out. I got it. It took a few months. I finally read it. I also loved it. After I finished the book, I called her. I was like, I want to talk about it, because I'm really I think I missed the bodies and borders thing. And she was like, No, it's this. It's that. It's this. So I want to and then I was like, Oh, I didn't miss it. I just don't think I would have, like, framed it that way. But I want to hear you talk about how you see this book as about bodies and borders and how those things fit together for you.

Sarah Aziza 26:06

Okay, yeah, I love that. And you know, authors don't necessarily pick the subtitles

Traci Thomas 26:13

I know I figured that, but like when she drew the connection for me, or she was helping me through it. I was like, Oh yeah, I did see that.

Sarah Aziza 26:22

Okay, oh, I'm so curious. I would have loved to hear that conversation. But so I think bodies, it's, it's obvious in some ways, right? Like, you mean, you see my body, like, from the beginning, like, that's a focal point. Like, you watch my body almost die, come back to life in this really complicated way. There's periods where, like, things are showing up, whether it's chronic pain or chronic illness. My body is like speaking a lot, and this book and recovery has really been a process of realizing, like, the body is a language. It's an archive, it's a community. There's like so much that we can discover and learn from our bodies. And you know, my body is what continued to point me back to just like the bodies that I come from. And what did my grandmother's body actually go through? Like at the beginning of the book, I'm remembering my grandmother as this soft, warm embrace, and, you know, she fed us this like, visceral source of comfort. But then we get deeper and we realize, you know, how many Palestinian bodies we've lost in since, you know, in the last century, from like British colonialism, like Zionist colonialism, things like that. And my body is not separate, even if I wasn't physically there. So there's a lot of just like that history coming, disrupting the present, and my body sort of being that portal to recognizing and understanding that to begin with, and really just grounding even my father and grandmother's story through. You know that was a lot of how I conducted my research was imagining into, pouring myself into this sort of the speculative nonfiction, learning everything I could about my grandmother's life, doing a ton of research to understand what the material conditions were, understanding like, how those things intersected in this one woman's life and and then I think, just like the body being an incredible vehicle, you know, I tried to write, like, close to, you know, close to the bone, in a sort of way of like, what would it have really been like to live her life while also leaving a lot of gaps and recognizing, I cannot know her experience fully, but there was this sort of sense of like collaboration with her memory in that way. And then borders. I mean, there's a lot of borders, the hollow half, like the half is a big theme of this idea of like, this sense of, like, separation from my identity as Palestinian, from the land, the border keeping us from our land, the borders that we draw around a single life thinking like, well, that that isn't so much my concern. I didn't live that experience. Just all of these ideas, like borders in the in the material, like political sense, but also just all the, all the, all the lines we draw around, like, like, you just said, like, that's those people's experience, and that was my father's life, and, yeah, just borders and nations and, like, the violence of the nation state and keeping people apart, and just all the ways these things sort of, like, intersect. That was, that was, like, a bit of an, like, free association, there's, there's more to it, I think. But I'm curious if any of any of those resonate, or if that made sense.

Traci Thomas 29:27

Yeah, for sure, they do. I think one of the ones that I started thinking about a lot was, like, the way that the personal and the political, like, there are borders between those things and that, like, those are their own bodies, and the ways that we sort of keep, like the ways that personal and political are both their own bodies and have their own borders, and like how that works, because I think you know, and there are parts of the book, and I won't, there's not a lot to spoil, but I won't spoil anything, but like your political awakening in college, and sort of like the way that you sort of bring your body to like, activism. I thought was really interesting. I do want to ask you a question, and I don't know if this is like polite, so I'm sorry if it's not, but I'm curious about, as a person who, like, has suffered from anorexia or like and like, eating disorders and these things that are so much about your own body, what it has been like for you to be publicly talking about these things and like knowing that people are seeing you and perceiving you in ways that I just have to imagine is difficult because you're so vulnerable in the book. So how is that for you?

Sarah Aziza 30:36

That's just a really astute question. I thought a lot about it right before the book came out. I tried not to think about it before then, you know, because, like, while I was, while I was writing, I was like, I just want to do what I feel like the book needs me to do, to really, like, honestly, reckon and, like, explore these ideas again. We already named him, but Kiese Laymon is, like, really instructive to me. Like his book Heavy the way, you know, it's so easy to just think about a reader's voyeurism and just, like, expose yourself in a way that's just like, I mean, some of the agents I talked to before I found the agent I worked with, like, really wanted to, like, exploit even more, if you can imagine, because I am very vulnerable.

Traci Thomas 31:19

I can't imagine. I'm like, wait, I don't want to know more. I know enough.

Sarah Aziza 31:27

Yeah, we're good, but yeah, just really, sort of like, there's this, like, almost like, fetishistic way you can talk about a woman's collar bones and body, and just sort of like this suffering, like, overly feminine, like, experience of like, a single woman being faint and weak, and then maybe eating and enjoying herself or something. But I really, I brought my body in. I kind of used it. I kind of referenced it earlier. It's a text. It's a language. I was learning it. I really wanted the reader to have the pieces that I did, to be able to like, think as seriously about trauma and trauma across time and like, those sort of, like, visceral connections, and the way our bodies tell the truth about, like, the nation we live in now, again, Kiese's book is an amazing, amazing, like, example of that, but just the way bodies show up and tell us things. So that was why I decided to put as much of me on the page as I did. I think I privileged the story and the thought and the exploration that I wanted to present to readers more than, because one thing that really drove the book, I think again, before I even knew it was a book, was I needed to understand things differently. I didn't need, not exactly answers, but I needed to reorient myself and the way I understood the world and my body and things like that. And as I was starting to put these things together, I was so blown away that I had to draw these, you know, I had to build this whole map, right, this web of, you know, over 100 you know, different thinkers and writers, you know, and like, years of therapy and listening to my body and all of these, like, somatic things. I'm like, I wish I had been given any of these tools, or any of these frameworks or a different way to think about myself or my body. So I really wanted to share as much of that as a resource just to be out in the world. It's just like one more place that somebody might stumble upon and, like, learn a little bit, like, maybe, you know, take some, you know, solace and comfort, or, like, wisdom, you know, without having to earn it the way I kind of paid for it. But to answer your question, I remember, I reminded myself throughout the process that this was an important priority for me. There are definitely things I didn't put in the book, but I did, kind of, I put myself out a bit on the limb, but it's because I really believed in the message and the art. And so I've just, I've been lucky that I've been able to intentionally choose, like, where I have appeared publicly. They've been mostly in, like, very supportive spaces, local bookstores, libraries, groups like that. And then I think also, because we have this ongoing genocide, and people are, like, so acutely aware of, like, the violence that's happening to Palestinians right now, I think people have come even more with tenderness towards me. So I've been grateful that I haven't, you know, and I also don't read comments or reviews or like, wherever those things might be happening. So so far, you know, as much as I felt pretty self conscious and exposed about my body, the way people directly interact with me has always been just like, very supportive and kind and and even the questions have been almost always more about the book and the work than like my individual like physical experience, which I'm grateful for, because I was bracing for more invasive conversations.

Traci Thomas 34:46

Yeah, well, that's why I was like, this might not be a polite question.

Sarah Aziza 34:51

You asked in polite way, I think.

Traci Thomas 34:53

Okay, good. I'm just so curious about it, because I think, like just being public period is challenging, right? Like just being a person who puts things into the world and has to answer questions or has to be on a stage or whatever, can be very challenging for most people. And I think, honestly, when I talked to Kiese about Heavy years ago, I had a similar question for him, which is like, what is it like for people to be staring at your body, when you are writing about your relationship, healthy and unhealthy, with your body. Like when I talk to authors who like write fiction or write about certain parts of their life, I don't ask them questions about things that aren't in the book, that are personal, even though I want to know because I'm nosy. But when you put your body in your book, I feel like, okay, well, that's fair game for me, like, in the same way that, like when I talked to Kamala Harris, she talked about their failure, about Palestine. And so I felt like that makes that a fair game question for me. And so I think, like, when you're writing about your body and struggles that you have, and controlling it or not controlling, and all of these things, but I'm also thinking like, well, if this is something that's hard for you, it's probably hard to talk about it also with strangers. So I don't know. I just, I'm always curious about that kind of conundrum.

Sarah Aziza 36:13

I really, I mean, the book came out in April, so I had several months of, like, tour. Like, it was very front loaded. I'm still doing events, but it was, like, very intense in, like, May, June, yeah, and I was in total shock at first, and I realized what the shock was was the difference between being a writer and being an author is very surreal and strange, especially in this like, world where, like, you know, people want you at least, to have a social media presence and be doing all these different things. And it's a very, I mean, I'm a little bit of a more extroverted person as far as writers go. But it's a it's an asset. I think about it a lot, like there are people who have like, you know, really severe anxiety and things like that. And like, the world is not as receptive or understanding of those things. So if I was any less outgoing, it would have been, I think, worse, but, yeah, no, it's, it is? It is a weird thing. But I think it's because at my core, I'm a writer, that I was like, the book needs me to go here. So Sarah will figure this out later. The book wants to go there. And for better or worse, there were some rough days.

Traci Thomas 37:19

For sure, I get it. I get it. I want to talk about the genocide in Palestine briefly, the like, the most current iteration from from 2023 kind of to the present. That doesn't really show up in the book, right? So the book, it goes, takes us to 2020 or like into 2020 a little bit past. I want to know as a writer, as a storyteller, knowing what world your book is entering versus what timeframe you're talking about in the book, how you were thinking about what you were saying, what you were saying to your audience, versus like, what was contemporaneous in the moment, I think, is sort of the question.

Sarah Aziza 38:00

So really, really good question, yeah, and it was a really tough question for me. I sold the book in, I think it was like, may or something, of 2023, okay? And it was like, semi proposal, I don't know it was like several chapters have been written, and then there was, like, an outline for the rest. And then October 7 happened. And then, honestly, like, I use the word genocide on October 16, and that's not because I'm a scholar of genocide. It's because I'm a Palestinian whose family is in Gaza, and I know the math. So from the very beginning, you know, I was like, and I have, like, a monitor and a laptop, so I was, it was like split screen. I was like, trying to write Palestine alive. While I was watching Palestine die, I was trying to write Gaza. I was trying to resurrect parts of Gaza that I had spent years like getting the pieces together, and I was trying to put them together, and I was watching those same buildings fall. I was watching the trees that my father was born under, like destroyed. And, I mean, it was just unbelievably, still is unbelievably painful, but it was, like, acute in a different way. Then, you know, I was, like, publishing a lot on the outside of, like, the book project and, and doing, you know, I was going to protests, and I was talking to family, and I was counting our dead, and I was trying to write this book, and, and so, yeah, knowing it was going to come out in 2025, I mean, it was just like, impossible to know, but also like it was also very possible to know, like there was going to be so much loss, at least by then. You know, I was watching, you know, eventually us going towards, you know, like 2024 and elections and things like that. And I was finishing the book in 2024 so I, I thought about it, but it didn't make sense for me to try to leap into 2024 2025 it would have felt forced and clumsy, and it would have anyway, been obsolete in its own way, by the time it came out. So I decided to stay true to sort of like the arc that made sense, which is like where I arrived as like someone who I felt like had at least come to some arrival about like how I now relate to Palestine and my identity. And it's about a position and, like a form of understanding, the responsibility of love, I feel is, like, really a huge part of this journey. So I ended up changing this is, this is where I really should get into. I ended up changing the last third of the book. I had a completely different, like, last chapter, and then the like and like epilogue was not a part of my plan, but the what I decided was I really wanted readers to leave the book with what I thought was like the equipment to look at the world today. There was plenty of history already in the book, but I wanted people to have more of an understanding of just all of the obstacles that Palestinians have faced in like their fight for self determination, and also all the ways in which Zionism has sort of like foreshadowed something like this. Because if you, if you look at like the founding fathers of Israel, and like the Zionist thinkers, they, many of them, have talked about and praised, theoretically, the idea of driving every Arab out so in so many ways, you know, there's so many people scratching their heads like we have no idea where all of this came from and why. Why are these things happening? And I wanted to give people, that's why I changed the last chapter to be called resistance, because there's always been resistance, and we've tried everything from nonviolent mass like demonstrations to hijacking planes to get people's attention. You know, like Leila Khaled, she said, like, we had to hijack planes. They didn't kill any. Like, people think hijacking they think 911 they would hijack planes land them as a way of getting on national news, because Palestine had basically been dismissed by the world. And she said, we needed people's attention. And I'm not, like, I'm not advocating for a hijacking planes, but people look at these isolated incidents of like, you know, why don't the Arabs want peace? Or, like, how could Israel do this? And I'm like, actually, all of the pieces have been in play. And I think that, like, if you really look at the history, you recognize that some form of resistance is natural and called for in order to, you know, just sort of like, be honest about what the power dynamics are, that Palestinians are unarmed, people who have no control over their borders, who have been dismissed and used and played with by on the global political scene for all of these years. And basically, we're at an impasse. And, yeah, I just, I just wanted people to understand how many doors have been shut and how many traps have been laid, and why, why there hasn't been quote, unquote peace yet. And just sort of like set people up to understand that, like we're in this unsustainable, again, impasse, where, if Israel had its way, it would just continue to delay while they colonize the West Bank and then, yeah, perhaps ethnically cleanse or genocide Gaza and their dream is greater Israel, which includes Syria and Iraq, and they have their way. So I wanted to set people up with a proper, with what I thought was like a more complete and often like overlooked history, and so they could understand a bit more the events today, and I think that resistance in some form is the highest form of love when the world as it exists is hostile to a dignified, safe life for the people that you love, whether it's black people in America or it's Palestinians in Palestine like resistance is called for if the reality is violent and hostile to life.

Traci Thomas 43:24

Yeah, when I posted about your book the first time, and you like commented and I had kind of compared it to Frankenstein, because I was reading Frankenstein at the time, and when I said that, I wasn't quite sure. But have to say, after finishing both books, I mean, there's certainly a conversation between what you're talking about, especially the last section, especially the resistance, especially the relationship between, you know, the creator and the creation, though it doesn't quite exactly map on, because Palestine existed before, you know, the creation of Israel, but that there is this like, deeply intimate relationship between people and place that has a response, you know, like that. I don't know, that was sort of a half baked idea when I put it on the internet, but in thinking about it, I've been thinking about it a lot more. And I think I can stand by it now.

Sarah Aziza 44:22

I mean, I think it's, I think it's a really incredible and amazing comparison. And, you know, I was reading something about Frankenstein the other day, and they were talking about how it was commentary on, like, just like, the apocalyptic nature of, like, the modern world and man's relationship to technology and things like that. And like, yeah, we're, we're in this, like, ghoulish, like, the world right now, honestly, is like, built on some very ghoulish, like, violent realities, and people like Palestinians, there are certain population groups that I think make uncomfortably plain for the rest of the world, like the reality of what our what our current system relies on. You know, and I think when black people rise up like it's a reminder, like it's a it's a haunting of like this country's past, and Palestinians are sort of like a contemporary hauunting of settler colonialism, this unfinished business of you're trying to dispossess people violently from their land. And when people have an ancient relationship with their land, they don't leave easily. They will fight till their last breath. And that's an understanding that I think somehow so many people don't understand, and they want us to be, you know. I mean, I think so many marginalized people have been given some version of this. Why can't you just be polite and behave and do it like this. You know, what we white like masters of the world decide are the scraps that you should have. Yeah, anyway. So yeah, I am for it. And I love it.

Traci Thomas 45:46

When I finished the book, I was like, well, this is an allegory for basically everything. So I feel like, I mean, because we did it for book club, I've been thinking about the book a ton. I actually can't stop thinking about the book. I can't stop seeing it in every little thing. But I think for me, one of the easiest, because some, a lot of the allegories don't quite map onto it all the way, like, it's like, okay, but I do feel like Palestinians as the creation feels like a very easy argument to make, right? And like, similarly, I'm sort of shocked to be honest with you that Frankenstein hasn't become sort of like the text of revolutionaries, right, like that. More people don't put it next to like Angela Davis, like, I'm just like it to me, feels like such a revolutionary text, and like a call for resistance. Anyway, I want to do, like such a hard shift, which is so annoying, but we have to get here, which is, how do you write? Where are you? How often? How many hours a day, music or no? Snacks or beverages, rituals, all of it.

Sarah Aziza 46:59

Ooh, yeah, it's sort of weirdly shifts around for me. For the longest time it was, like, early morning was the best time, because I can get so, like, caught up in everything. So getting up early in the world is quieter. I'm really grateful that I have a room that's sort of like dedicated to writing, because we have three rooms in our little Brooklyn apartment, and we have no kids, so one of them can be for writing. So I can go in there and know that it'll be quiet, and I have a desk. It's a pretty big one. It's sometimes, you know, I have one of those collapsible. It can be a standing, can be a sitting, at the chronic pain stuff I'm dealing with, definitely things are around me. Sometimes it's snacks. I like salty and crunchy. So like pretzels, nuts, things like that. But lots of tea like it's embarrassing.

Traci Thomas 47:55

What kind of tea, talk tea. I love when someone says, whenever someone says coffee, I'm like, move on. But tea, let's talk

Sarah Aziza 48:01

Alright, um, Puer Tea Is that what it has, or Puer, I think is what it's called. It's like this fermented black tea, it's really earthy

Traci Thomas 48:08

oh, yeah, somebody else talked about that.

Sarah Aziza 48:11

I need to make sure I'm pronouncing it right. But it's really good. It's got like, caramel notes and stuff, so it's pretty strong, but I think it's like, a little smoother than, like, a coffee, okay? Then lots and lots of maramia, which is sage tea, which I talked about my grandmother serving us. It's, it's, yeah, herbal and very soothing.

Traci Thomas 48:35

Anything in your tea? Do you put, like a honey or a cream, or anything?

Sarah Aziza 48:40

Um, yes, I'll put, I'll put, like a oat milk or something in the black teas. And then sage sort of just wants to be on its own, although sometimes I mix it with peppermint tea, but I make like a pot of sage and peppermint together. It's just, we're doing a lot of cooling off of the psychic system. So these, like cooling teas are good for me, and, like, just tons of water, I think when I'm anxious, which is most of the time, because I'm writing about these sort of things that are hard, I'm also, like, drinking a lot of water.

Traci Thomas 49:11

Do you have any rituals that take you out of the writing back into the world?

Sarah Aziza 49:17

Yeah, that's important. It can be as simple as, like, I live on a quiet street, but I could walk a couple streets down and there's like, a really noisy street with like, 10 supermarkets and stuff. And I sometimes I just need to be, like, jostled. Like I used that word at the beginning. I'm just like, yeah, oh, get out of your head. Like, look at there's literally hundreds of people, like, living their own dramatic lives. It's just like, sort of like, brings me out. I'll like, yeah, just think of a random errand. And I'm like, go mail a letter or something, just so I can, like, be in the world for a second. Or there's a dog park that I'll go watch puppies. I don't have my own puppy, have a cat, but just anything that, like, gets me into someone else's subjectivity for a second, yeah. Or I'll do some, like, breathing exercises.

Traci Thomas 49:58

Any words you can't spell correctly on the first try?

Sarah Aziza 50:03

Bureaucracy.

Traci Thomas 50:03

Oh, impossible.

Sarah Aziza 50:04

Hands down. Yeah, that's the only one that comes to mind. There's plenty.

Traci Thomas 50:09

That's a good one. Do you know what comes next for you?

Sarah Aziza 50:13

Ooh, um, I would like to, I can't say that I know, although, like I'm working on some essays now. There was just a lot of like, thinking that I've been doing over the past two years, of like, what's our relationship to witness having so much exposure to these, these, you know, they call it the first livestream genocide, not the first genocide, but the first live streamed, real time genocide. Yeah. So to have so much insight and exposure into these, like, deeply intimate, deeply violent moments in people's lives and be intertwined with it in some ways, and also feel so helpless. How do we wrestle through like, that sense of helplessness and what's like most ethical way to move through this technological age of mass violence? So I've been writing some about that and doing some research. I would love to do. I've been writing poetry very privately. I would love to do something in more poetry fiction, but this non fiction muscle is, like, very active, yeah.

Traci Thomas 51:09

I eagerly await whatever that is. Oh, thank you, um, what about the book's been out for a while? I don't always get to ask this question, but I am curious who's, like, the coolest person to you who's expressed interest or talked about the book in the world.

Sarah Aziza 51:25

Oh wow, that's a that's a good one. There have been a few, a few really touching ones, I think just Palestinians, like far and wide, that have gotten this book into their hands. It's just really moving to hear that like, they found it moving. I think I was really honored that Kiese read and blurbed it early on that, like, that was a huge like, wow moment. There's a couple others that I'm blanking on, but just like, you know, just people who I deeply admire, their intellect, who have, like, mentioned that they enjoyed my book. And I'm just like, start like, you know, starstruck, but I mean nerdy ones, nerdy ones.

Traci Thomas 52:08

Yeah, this is a nerdy podcast. Is there anything that's not in the book that you wish could have been?

Sarah Aziza 52:13

No, I think, I think it's doing enough. I think, you know, there's like, more to be explored, where, when, when it comes to like, queerness, desire, pleasure, those are some of the things that I took out to make room for, like the resistance chapter, because I think resistance needs to be foregrounded. But desire and pleasure, all of those things are integral, and they're like, really, I say it in like the epilogue like, those are Palestinian too. It's not just our grief and our suffering and our need for evolution, but it's also like joy, things like that. So I hope to do more writing and exploring of those, those topics.

Traci Thomas 52:50

Maybe that can go in the witness stuff. I'll let you figure that out. You're the writer. I'm not a writer.

Sarah Aziza 52:57

Oh, this is when that comes in handy.

Traci Thomas 52:59

Here's my last question for you, if you could have one person dead or alive read the book, who would you want it to be?

Sarah Aziza 53:07

Oh, I think my [illegible] and my grandmother like I wish, I wish she could be there. But, you know, I also know that in some way she is, she is here, and I hope that she just feels like deeply loved.

Traci Thomas 53:23

I love that. Well, everybody The Hollow Half is out in the world. Wherever you get your books, you can get it, like I mentioned before, if you're doing audio, I think you should do both. I don't want to tell people what to do. I just think you might get more out of it if you have the opportunities to flip through the pages. Also, some of the stuff is oriented really interesting on the page, like a lot of blank space or full space. You know, there's things that are crossed out. You just might want to look at it if that's available to you. Sarah, thank you so much for being here. This was amazing. Thank you so much. I really appreciate it and everyone else, we will see you in The Stacks.

Thank you all so much for listening, and thank you again to Sarah Aziza for joining the show. I'd also like to say a huge thank you to Megan Fishman for making this episode possible. Our book club pick for November is We the Animals by Justin Torres with our guest, Mikey Friedman, returning on Wednesday, November 26. If you love The Stacks and want inside access to it. Head to patreon.com to join The Stacks Pack and check out my newsletter at Tracithomas.substack.com make sure you're subscribed to The Stacks wherever you listen to your podcasts, and if you're listening through Apple Podcasts or Spotify, please leave us a rating and a review for more from The Stacks. Follow us on social media @thestackspod, on Instagram, Threads, Tiktok and now YouTube, and you can check out our website at thestackspodcast.com. This episode of The Stacks was edited by Christian Duenas, with production assistance from Sahara Clement. Our graphic designer is Robin McCreight, and our theme music is from Tagirijus. The Stacks is created and produced by me, Traci Thomas.