Ep. 403 Being Heartbroken Is Annoying with Alejandro Varela

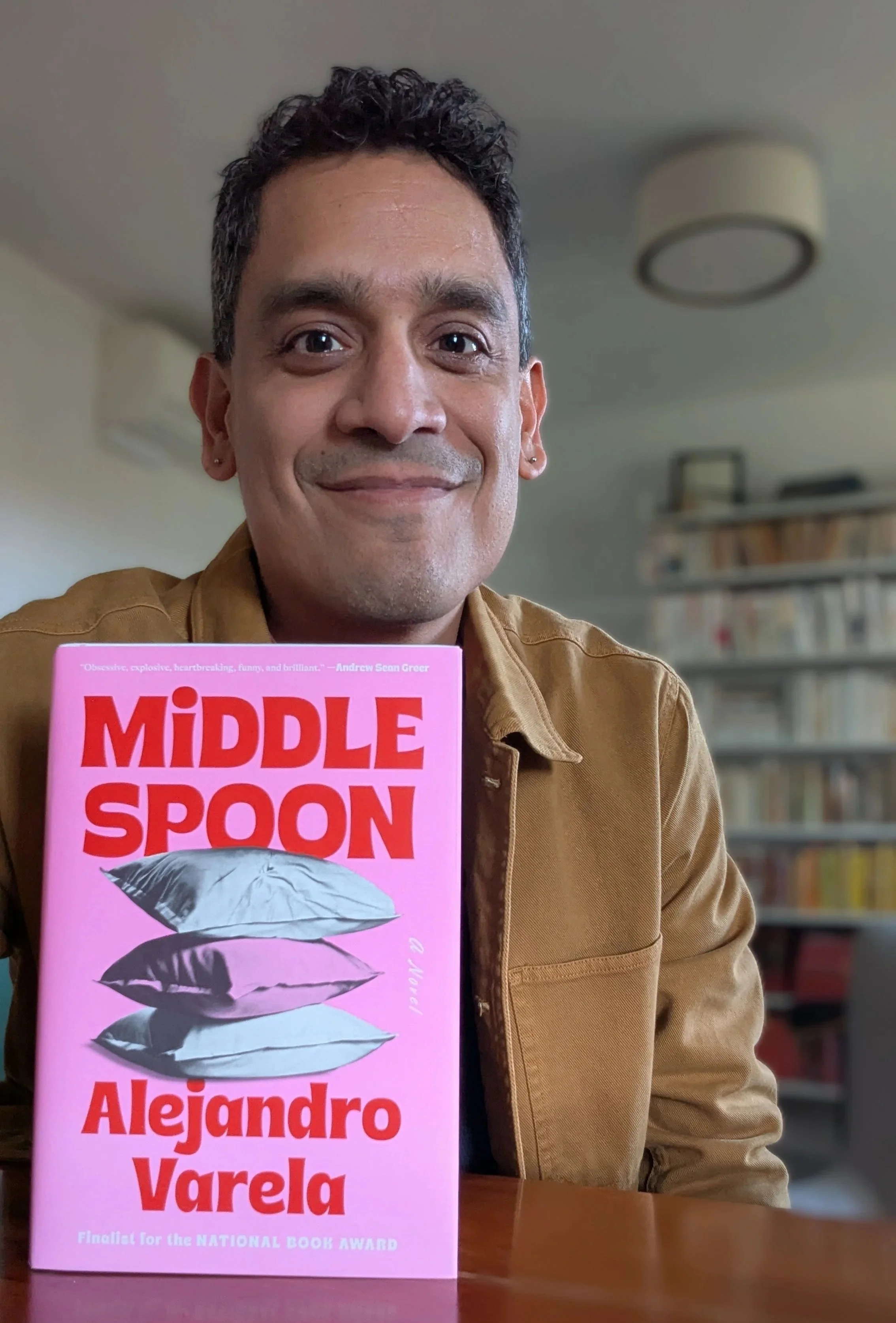

Today on The Stacks, we are joined by National Book Award finalist Alejandro Varela to talk about his newest novel, Middle Spoon. Humorously exploring unconventional relationships and complexities of polyamory, this novel follows Alejandro’s unnamed narrator, a married man navigating heartbreak after his boyfriend abruptly dumps him. We discuss why he wanted to write about heartbreak, how he brought more of himself to this book, and why it was important to him to depict OCD correctly.

The Stacks Book Club pick for December is Friday Night Lights: A Town, a Team, and a Dream by H.G. Bissinger. We will discuss the book on Wednesday, December 31st, with Joel Anderson returning as our guest.

LISTEN NOW

Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Google Podcasts | Overcast | Stitcher | Transcript

Everything we talk about on today’s episode can be found below in the show notes and on Bookshop.org and Amazon.

Middle Spoon by Alejandro Varela

The Town of Babylon by Alejandro Varela

The People Who Report More Stress by Alejandro Varela

The Book of Delights by Ross Gay

“The Hashtag That Changed the Oscars: An Oral History” (Reggie Ugwu, The New York Times)

University of Washington (Seattle, WA)

“We Are the World” by USA for Africa

The Greatest Night in Pop (Bao Nguyen, 2024)

“Stare at Me” by JANE HANDCOCK ft. Anderson.Paak

Wittgenstein's Nephew by Thomas Bernhard

The Loser by Thomas Bernhard

Extinction by Thomas Bernhard

Middle Spoon by Alejandro Varela (audiobook)

To support The Stacks and find out more from this week’s sponsors, click here.

Connect with Alejandro: Instagram | Website | Bluesky

Connect with The Stacks: Instagram | Threads | Shop | Patreon | Goodreads | Substack | Youtube | Subscribe

To contribute to The Stacks, join The Stacks Pack, and get exclusive perks, check out our Patreon page. If you prefer to support the show with a one-time contribution, go to paypal.me/thestackspod.

The Stacks participates in affiliate programs. We receive a small commission when products are purchased through links on this website.

TRANSCRIPT

*Due to the nature of podcast advertising, these timestamps are not 100% accurate and will vary.

Alejandro Varela 0:00

The DMs started, you know, started with the first book, and they were always really heartfelt. I feel like you wrote about my life as a queer kid, as a brown kid, as a suburban kid, so on and so forth. And I didn't, I don't sit down and think, Oh, I I have to write for people who might connect with me. I think I'm writing about some pretty universal stuff that hasn't gotten a lot of attention, maybe, but deserves more attention. And so the DMs, in that way, they're really heartening. They personally, they are validating. They make me think that I've chosen a path, a career, where I'm doing more good than harm, and that's, you know, that's all I ever want. But, yeah, it's quite heartening, heartening, and it makes me want to keep writing.

Traci Thomas 0:49

Welcome to The Stacks, a podcast about books and the people who read them. I'm your host, Traci Thomas, and today we are joined by National Book Award finalist Alejandro Varela to discuss his newest book, Middle Spoon. Humorously exploring unconventional relationships and the complexities of polyamory, this novel follows Alejandro's unnamed narrator, a married man with two kids, as he struggles to navigate heartbreak and judgment after his boyfriend abruptly dumps him. Today, Alejandro and I discuss why he wanted to write this heartbreak novel, how he sees himself as a public policy advocate whose medium is fiction, and how his desire to be liked has transformed him into a prolific author. Our book club pick for December is Friday Night Lights: A town, a team and a dream by H G bisser. We will discuss that book on Wednesday, December 31 with Joel Anderson. Everything we talk about on each episode of the stacks is linked in our show notes. And if you like this podcast and you want more bookish content and community, consider joining the stacks pack on Patreon and subscribing to my newsletter, unstacked on sub stack, each place offers different perks, like community conversations, virtual book clubs, writing hot takes and bonus episodes, and your support makes it possible for me to make the stacks every single week. So head to patreon.com/thestacks to join the Stacks Pack community and check out my newsletter at TraciThomas.substack.com. All right, now it's time for my conversation with Alejandro Varela.

Alright, everybody. I'm so excited. I am joined today by Alejandro Varela, his latest book is called Middle Spoon, guys, I sort of loved it. I didn't think I was going to it's like, if you told me about the book, I would probably be like, That's not for me, but I really liked it. So, Alejandro, welcome to the stacks.

Alejandro Varela 2:33

Thanks, Traci. It's really nice to be here.

Traci Thomas 2:38

That's sort of like a mean introduction, but I mean it as a compliment, because I feel like I'm such a like weirdo when it comes to fiction. But you sort of sold me on the book at the Texas Book Festival when I got to see you and Tiana Clark, friend of the show, on a panel. So can you tell folks in a similar way that you did it at the festival. What this book is about?

Alejandro Varela 3:03

So a middle aged man has his heart broken for the first time, and he is going through it. He's in a lot of pain. He's essentially reverted to being a 17 year old, but with the perspective of a middle aged person. So now he's trying to intellectualize the pain away. And on the advice of his therapists, he has two, and those therapists do not know about each other. He decides to write down what he's feeling, and in a sort of modern day journal way, he writes emails to the guy who broke his heart, Ben, and he never sends any of those emails. And those emails are mostly to Ben, but they're also to a slew of other folks, his mom, his kids, the Academy of Motion, the editor of the New York Times, the Department of Sanitation. And this is how he, sort of processes life, and again, deals with the anxiety and plot twist, or, I guess not, because it happens at the beginning. We find out the narrator is happily married with children, and so this was a polyamorous situation that kind of complicates the grief in a way, because can he get empathy if he has such a perfect life? how is he going to get through this?

Traci Thomas 4:16

Okay, I think the question on my mind and everyone's mind is, how did you come to this story? Where did you get the idea for this book? When did you get the idea for this book?

Alejandro Varela 4:26

I in December of 2022 was going through. I had already written my first two books. The first one was published the town of Babylon, and the second one was coming out in a few months, and I was contracted to write two other books, and I started writing. The first one, got 30,000 words in. I was super excited, and then I went through a rough time in my life, experienced a bit of heartbreak, and so I sat down and. And was like, I This is wild. I I don't know what to do with this, with this sadness. And so I thought, let me write about this, because this is really unique. And since I hadn't experienced it before, not in that way, I've since thought about it. And I do believe in when I was much younger, I had some heartbreak moments, but not like that. And so I started interviewing people, everyone, everyone, everyone in my life, perfect strangers at parties, and I would ask everyone, have you ever had your heart broken? And I know I sound naive, but I wasn't expecting absolutely everyone to say, yes. I wasn't expecting everyone to say, I feel like it was just yesterday. I wasn't expecting everyone to say, Oh my God. I think I could cry right now thinking about it. And that really moved me. And I was thinking about how there are 8 billion people on this earth, and if everyone is going through this, or if everyone has this at the surface and they haven't processed. I mean, you can take bereavement leave if a parent dies, sure. But what do you say to your boss if you get dumped? And what do you say to your boss if you get dumped and it's like your lover and not your partner, you know? Yeah, like you still have to function as well. So I just was really interested in exploring these feelings. And to your point earlier, where you said that the introduction sounded a little mean. This is the first in my three books, well maybe what I share with the narrator is a desire to be liked in this world or to get validation. And we can dive into, you know, the brownness and queerness and immigrant kid of it of it all, but with this book, I said, No, I don't need to be liked. And also being heartbroken is annoying, like going through it is really taxing, not just on yourself, but on the people around you. And I thought, if I'm going to write this authentically, this person isn't going to be likable all the time.

Traci Thomas 7:00

I thought he was likable. You had kind of given this preface of like, he's annoying, and people think he's annoying. And even when I reached out to you, I was like, I'm 30% of the book. I really like it. I think you should come on the show. And you were like, I hope you don't find him annoying later. I didn't find him annoying. I felt like he was, like a sad boy. And like, sometimes I was a little bit like, come on, narrator, like you could do it, but I never was like ugh about him.

Alejandro Varela 7:30

Well, I guess I will say I'm I'm happy to hear that, because I feel like the majority of the feedback I've been getting is like, he's a tough narrator. It's not so easy to sit with him compared to your other books, but I couldn't put it down. And so that felt, that feels like actually a great compliment. And I've been enjoying that feedback because I set out to do that, but I didn't know if I could pull it off. I didn't know if I could make someone that, you know, borderline annoying, let's say, or, yeah, like, self involved. But that's just it like, this is what happens when you are heartbroken. The world is falling apart and and the world is just fine. I mean, the world is a mess, but not because of your heartbreak, but you think it is, and everyone else looks at you and they're like, Oh, the empathy comes out, and then the next wave is sort of like they look at you with these with these eyes that, if you know your people well, you're like, Oh, shoot. They're done with this. They don't want to hear this anymore. And then, yeah, that actually is, I think it is great if you don't take it personally, or even if you do, because it says these people aren't worried about me. That means I'm going to be okay. Because if they were truly worried, then I should be worried. It's kind of like I am afraid to fly. And every time I'm about to get on the plane. I get really nervous, and then I search for reassurance, and then I get on the plane. And I think, Wait a second, if my husband really thought I was going to die, he wouldn't have let me get on this plane, right? So, so I need to just chill out.

Traci Thomas 8:57

That's so funny. I have, I have some plane anxiety, but the most confident I ever feel on a plane is when there's like, sort of bad turbulence, and the person next to me is visibly more scared than I am, and then I'm like, we're gonna be okay. I feel like I turn into like, Oh, it's fine. Like, chill out. Like, why are you being so dramatic? Even though I'm sitting there, like, this is the end of my life. I am dying. This is coming down 30,000 feet is a long way to fall. But then the person next to me, I see them, like, grab the thing, and I'm like, oh, it's like, kind of look over and I'm like, It's okay, sweetheart.

Alejandro Varela 9:29

The parent comes out. The parent comes out.

Traci Thomas 9:33

Okay, as a person who interviews people for their work, I need to know what kind of questions you were asking, and specifically when you were interviewing strangers at parties, what were you saying? Were you like, Hey, I'm writing a book on heartbreak. Or were you just like, hi, nice to meet you. Have you ever been heartbroken? And then, like, what follow up? Like, what? What were these conversations?

Alejandro Varela 9:53

Yeah, so I would, you know, a little small talk. First, how you doing? What do you do for a living? Okay, that's. Nice. Okay, what are you doing for the holidays? Oh, and that's really nice. How are you doing? And then I think in moments of vulnerability, I would say, You know what, I'm not doing great. Oh, what is it? I said, I kind of just had my heart broken, and I'm going through it. And they're like, Oh, honey. So the really great people would be like, Oh honey, and take my hand, or do you want to talk about it? And other people would be like, Oh, that's the worst. And then I would say, oh, so have you had your heart broken? And they're like, Are you kidding me? How much time do you so that's so I had. I would say, easily, three dozen of those conversations and and so then I started to notice feelings and themes that were similar, and ideas and the desperation too. And I always ask the same question, which the narrator does in the book as well. I would say, How long does it last? And because my background is in public health, and I like, you know, large denominators. So I'm like, okay, one person, it's going to last 10 years, that's the outlier. And one person, it's going to last one day also an outlier. But what's the average here? What are we talking about? Because I can mentally prepare to be in my feelings if I know there's an end date and and so that was really helpful. And some people were like, You know what? It always kind of stays with you. And I'm like, don't say that to me. They'd be like, but no, no, no, no. It's It's not like that. It just sort of stays with you as a memory, and it comes up, and it can even bring you some sort of happiness sometimes, because it's a chapter in your life that you remember and it's ended, but it's always there. And yeah, some people are like, Oh, you're gonna wake up one day and you're gonna be like, Oh, I don't feel it anymore. And I was like, Oh, yes, how long? And they'd be like, I could be a few weeks. It could be a few months, I'm not gonna lie

Traci Thomas 11:43

My therapist told me, you can get over anything in a year. Yeah, but I only have one therapist, so maybe I need to get a second therapist and be like, what's your assessment? Because I'm obsessed with two therapists

Alejandro Varela 11:56

I know. Well, I really wanted to lean into the anxiety of this character, and I thought like, sort of ratchet up right. Keep going. Keep going, keep going. And the two therapist was something that I thought was kind of funny, and it happened to me years ago that I was transitioning out of therapy, and I found another therapist, and so they overlapped for and I remember telling my friend Josh, and he's like, that is the premise for a book.

Traci Thomas 12:28

I have a friend who has two therapists. I just found this out, and then I heard about and then I heard you say this in your book, and I reached out to them, and I was like, do your therapists know about each other? And they were like, they do not. I just throw back, I'm obsessed. But I am obsessed. I'm just obsessed with this idea of having two secret therapists, because I feel like I don't know. I just feel like it's so like, I sort of want two therapists now, like I sort of want to know, Are you who's the better therapist? Like, I would be pitting them against each other. I would say the exact same sentence and see how they responded and be like, Oh, interesting, not as effective as as Fred or whatever.

Alejandro Varela 13:09

Well, without, you know, giving too much away, we do learn over time that there's a reason why. I mean, this man is constantly seeking from for reassurances, from life in general, for everything, and it has something to do with his mental health, but it also helped with this motif of middle right. He's not just caught between two partners and two kids and parents and children and generations and socio economic status, but between two therapists as well, and I, and I, yeah, I love it. That was kind of fun.

Traci Thomas 13:42

It's great you keep talking about this, like need for validation, or like wanting to be liked. So I want to hear more about that. You sort of said we could talk about this later. So what is it? What is it about that that is interesting to you, to explore?

Alejandro Varela 13:56

So I do have that in common with the narrator, I think, to varying degrees. I believe it has something to do with my socialization, how I was raised. For more on that, read the town of Babylon. No

Traci Thomas 14:12

I gotta go back and read the town of Babylon. I never read it, so I'm, like, really excited. I'm excited to go back into your whole archive and, like, read the other two books.

Alejandro Varela 14:20

Thank you. No, but it I was raised in a working class mostly white town on Long Island. We're the only latine family in the immediate area. Things like that, being queer and closeted, all of those things, I think, made it so that I felt very much on the outskirts of, you know, we call it marginalization from society, but in daily practice, it just meant that, like, I felt like I couldn't truly participate in everything that was going on around me, and so I tried extra hard to make up for it by being, wanting to be popular, and wanting attention and and. Wanting validation. And so then it became this kind of cycle of searching for reassurance and but in some ways, has made me a great writer. Geez, did I say great? I just meant, has made me a good writer.

Traci Thomas 15:13

You are a great writer. I like great. I like great. Stick with it. Okay. This is making you unlikable. You know, working on in our therapy session as your third therapist

Alejandro Varela 15:26

I think it it means that I was observing for so long and not fully participating, and I'm talking like being in a college class and just not being able to raise my hand, because I'm so afraid of being wrong. I'm so afraid of being like embarrassed, and make it, making it through almost four years of like that, and and so, but I had almost 40 years worth of conversations and ideas and things that I didn't always express. So when people are like, you're so prolific, your three books in three years or something, yeah, and I'm like, it's gonna run out. I just have, I have 40 years worth of ideas and notes that I'm I need to get down. And then, yeah, and then we'll see what's next.

Traci Thomas 16:15

Do you feel like you have books four or five? Like, do you feel like you have these things you're you've got more already that you're ready to do. And say,

Alejandro Varela 16:23

I have eight books fiction that I want to write, and I have one nonfiction book that I want to start soon. I quit drinking. My birthday was on Saturday.

Traci Thomas 16:36

Oh, right, you said, and you quit drinking.

Alejandro Varela 16:38

Yeah, so the in the in the lead up, I decided that that would be my last day of alcohol. And this morning, if you can believe it, I was thinking that I would like to chronicle a year without alcohol. And so every day, I like to write a little bit about it, but in my way, also explore society and my upbringing and see what comes of it. So maybe that'll be the first book of nonfiction.

Traci Thomas 17:03

It's like Ross gay delight books of delight, but it's like your book of sobriety or whatever. It's not a great title, don't I don't think you need that. I think we can workshop that a little better. I love that. I love that. One of the things you said in Texas at the festival was you talked about how when you wrote your first two books, everybody would come to you and be like, this is you like, this is this is really like, this is Alejandro. This is auto fiction. And when you sat down to write middlespoon, you decided to actually put more of yourself in that book than maybe you did for the first two and I'm curious how that has felt to you as people receive the book, like knowing that more of you is maybe on the page than your first two books, and how I don't know. I'm just fascinated with people thinking they know people. And so I'm wondering if it, if it feels different knowing that you did actually put yourself on the page more in this one

Alejandro Varela 18:04

I mean, absolutely, if, if you're my best friend or my dad or my mom, you know, in the first two books, more or less what's me and what's not me, where I'm borrowing from. But I would argue that in the first two books, what I have in common with the people is that I'm brown and human and queer and and a few and a few political beliefs. But there are, you know, short stories, 13 stories of 13 plots of things that never happened to me, and then an entire novel of things that never happened to me. And I thought that's what fiction is like. I wasn't. I didn't want to be like an old Greek woman. I didn't want my narrator to be an old Greek woman. And so I wrote in that way. What I knew, that perspective with this book, like I said, I borrowed from a difficult moment in my life, and then I went with it. And by the way, the kind of difficult moment, the pain I was going through was very short lived, very short lived. And then I had to finish writing a book, no longer feeling pain, feeling that, right, right? So then I had to go a little like, method, Daniel Day Lewis, and yeah, and like, what would this heartbroken person have in their pockets, right, you know? And so, and, and that was an interesting exercise, and it was kind of fun, but, like, as I thought, you know, Clay was not data, of course, yes. And so clavian, yeah. So clavis is just a wonderful person, and we were in San Antonio Book Festival a few years ago, and I was telling her about this idea, I'm like an epistolary novel about heartbreak and polyamory and public health. It's kind of weird. And she said, You've earned the right to follow your weird. She said, you have two books under your belt. Just write what you want to write. I've always felt I've written what I wanted to write, but maybe this book, that idea that it's it's too different, it's too out. Of the mainstream, it's too niche. Made me worried. But honestly, I was like, There's nothing more universal than grief.

Traci Thomas 20:10

Yeah, I mean, I don't think this book feels like that at all, like I feel like it feels very universal. I mean, I was taking notes about things that as I was taking the notes, I was like, You're doing the thing that white people do, where you make someone else's story about you, you know. Like, I was like, thinking, I was like, writing things down about like, men. And I was like, This is why we're having the male loneliness epidemic, because men are stuck in like, certain norms of heteronormativity and blah, blah, blah. And I was like, this is literally a book about queer people, and you're trying to make it about straight men, like, so like, I feel like it does have that, you know, almost universal feeling, because it is, like, so specific, you know,

Alejandro Varela 20:47

I went to winter Institute in February, you know, okay, the American book seller Association, yeah, and it was my first time out with the book in the world. And it was several months before publication, and a handful of bookstore owners walked over to me and said, what you said at the top of the show? I didn't think I would like this. I read the description, and I still didn't think I would like it, and then I got in a few chapters, and I was hooked, and that made me feel really good. But I still think there are a lot of people who will read the description and then it's done there, you know, like they're just not going to take a chance. And so I thought that's that was what was going to happen, you know. And so I didn't, I was a little concerned a queer polyamory story. I mean, give me a break, yeah, and, but, I mean, I could have made it a gay, a gay heartbreak story, not not poly, not polyamorous. I could have made it a straight, you know. I could have made it a white, you know, like I could have kept making it more palatable for the mainstream, right? And I, but I pick up a book because I'm like, I want a new experience. And so that was also a challenge when I was writing it this narrator that I was less concerned with being lovable or being, you know, endearing, and also really thinking, how can I bring someone across the aisle here? I don't even mean a political aisle, but just, I'm in pain. You're in pain. Let's just focus on that. When I was teaching public health grad school, we used to do a case study and several case studies in a semester, and one of them was around trans health. This was in like, 2012 and my students were, there was a lot of transphobia in the room. Let's just say yeah. And then we would, I would make the argument that, like, Okay, you're not, you're not comfortable. You are. Don't agree. You, quote, unquote, have values. But can we agree that no one should be killed, right like because at the time that was the conversation around it was that we were focusing on a national day of trans remembrance, and we started there we can agree that. And I think that has been my way of thinking about not just public health, but human relations and politics. What can we agree on? And so I thought if I could write a book where we can agree on the pain of this great and if I can write a book where we can think about like the OCD of you know what I mean, there's the various ways in which we can just say we agree on these things, and so then the rest actually becomes easier to kind of take it.

Traci Thomas 23:19

Yeah, I think also for me, in the reading experience, while you're writing about something that I feel like everyone writes about heartbreak, right? Like every song is about heartbreak, every movie is about heartbreak, this book feels extremely fresh. It doesn't feel like the same like you're hitting the same beats as everyone else. And I think some of that is that, while we've been talking about it as, like, this heartbreak book, it's really funny, like, the narrator is like, really, like, I don't know. Okay, I'm gonna use this word that I don't mean it in this way, but I'm gonna use it colloquially. Like you said he was annoying, but he's not annoying. He's just like, dumb Do you know what I mean? Like, he just says dumb shit, and I'm like, Stop, like, You're so embarrassing, but it's like, endearing and it's enjoyable to be with him, and I think that feels really fresh, because I know at least for myself, sometimes when I am at my worst, like when I'm the most annoyed with someone else, or, like, feeling The most like, uh, I am the funniest because I'm saying the dumbest shit, and sometimes on purpose, like to get a laugh, you know, like I'm talking to my best friend, and then I'm like that. I don't know, I can't think of a good example, but I feel like you really tapped into that part of it, too. Like the tangents he goes on, and sort of the ideas that he gets into are just so they feel so correct in moments of crisis. And I think that freshness also makes the book feel like people can relate to it or come into it, because who hasn't had hot, hot, hot takes about the Oscars? You. Know, Like, you have a whole section of the book of like, how we need to rework the best acting categories and all of this. And you have like, this person deserves this. This person deserves that. And I was reading that section being like, yes, of course, because you could be feeling sad, but also you could still be feeling extremely self righteous about the Oscars at any given moment. And if you weren't, I would be like, oh, this person sucks. They're no fun at all, you know. Like, why would anyone ever be in a relationship with this person who doesn't have any insane takes about, you know, sanitation or whatever,

Alejandro Varela 25:30

and but also, how do we or how, as a writer, I guess for me, I also thought, How do I make these digressions circle back so that they feel like you've left the path, but they're so related to the path we were on. And I'd like to say that with most of them, I I was able to do that, maybe not every single one. But you know, the pop culture digressions have a lot to do with the fact that we're talking about a narrator who is really concerned with equity in life, right? And how it has affected him and how it has affected his brain and his ability to process stress and all that. And there is no every day we are told, who has value and who doesn't. That's what the pop and pop popular culture, right? Right? So we're constantly being told this has value. This is the most important thing. And so I think it's almost that's why, when people are like, well, you know, so many terrible things are happening in this world. Why Oscar's so white? Yeah, that's a take, and I don't necessarily disagree with that, but sometimes I also feel like, if the things that stand in for what is most important in culture feel equitable. Then, you know, then we can measure ourselves against a better equity bar, as opposed to what we're seeing or what we've been living through.

Traci Thomas 26:50

Yeah, okay, let's take a quick break, and then we're going to come right back. Okay, we're back. One of the things we've talked about in this book is how the author is anxious, and it comes out later in the book that he has OCD. And this might be a stupid question, but what is the clinical difference between these two things?

Alejandro Varela 27:14

Okay, while I was writing the book, I learned about OCD all my life. I think we've used OCD in a very jokey way, like I'll do the dishwasher. I'm OCD.

Traci Thomas 27:24

Also we use anxiety in that way too. Now I feel like anxiety and OCD are both sort of just like things we say, but they have real definitions

Alejandro Varela 27:32

Right, and to your point earlier about the book being funny, first of all, thank you. But also anxiety OCD all sorts of mental illness. They are quite terrible to live through, very debilitating, painful, a big tax on you, not just psychologically, but physically as well. And but on the page, they're quite funny. They can be quite funny. And I think if you that's what I did. I tried to lean into that anxiety, and in this case, OCD as well, and because I thought they would undercut some of the gravity of the pain and also the professorial stuff, the digressions. Anxiety is one thing, and a lot of us feel or have anxiety, or have been diagnosed with anxiety, and we go to a therapist and we talk about all the things that are on our minds and all the things that we're worried about all the time. OCD, which I learned about while writing this book. Learned with more intention. I mean, is the 10th most common illness in the world according to the World Health Organization. Wow. Now I don't know if the United States believes in the World Health Organization anymore.

Traci Thomas 28:36

No, of course not. Who?

Alejandro Varela 28:38

I was like, Wait, the 10th most common in the world. I need to know more about this. And what I learned is that if you can picture a psych like a wheel or a circular pattern, and at the very top is obsession. I am worried that everyone hates me and my work. I'm worried my work sucks. Everyone hates it, and now I'm anxious, and this is like split second stuff right far across my mind. Now I'm super anxious about it. My compulsion will be I'm going to either ruminate and come up with an entire theory about what that interaction with Traci meant, and what it really is saying about me and my work, taking control of that moment by coming up with a theory, then leads to a this is the last step in the cycle here. Leads to a momentary relief, ah, and you feel control, even if it sucks, at least you took control the narrative. I mean, you literally wrote the narrative in your head. And then guess what? You go right back to obsession, because you solved nothing. So then it becomes a cycle. The thing that might change is how quickly you move through them or in the compulsive part, what what your compulsion is. It could be calling your best friend and asking for reassurance, and every time they talk you down, they validate that obsession. So then the cycle continues. It could be going to a therapist. That's why I said most people go with OCD, go to a therapist, talk about their anxiety, and a lot of therapists aren't trained to distinguish between the difference, and so they're validating your anxieties by reassuring you constantly that reassurance is a compulsion. And so it could be sex, it could be porn, it could be alcohol, it could be any number of things that in the moment give you control, so you can feel temporary relief, and then back to the obsession. So what I learned is that there are very specific evidence based treatments, namely around exposure therapy, where you interrupt right at obsession. You never get to anxiety the moment the thought crosses your mind. Because what OCD is is like this animal on your back, an albatross, a monkey. I don't know which the metaphor is, and it's telling you you don't have all the information, and you need all the information, and if you don't have that information, you're in danger. I need to know how that person feels. I need to know why that person said, Let's talk later. Oh my god, don't do that to someone with OCD. I need to talk to you. Do you have time next week? What? I'm like, right now, so, so that's so I also thought that lent itself to this with this guy's personality too, right? This narrator is trying, he wants answers to everything he wants, instead of just feeling and not knowing what's coming. He's like, I need to know and I need to abbreviate this torture. So he's trying to intellectualize it all away. I think. I know.

Traci Thomas 31:26

I mean, I feel like what you just described, probably everyone listening is like, Wait, do I have OCD? I mean, at least, at least I'm feeling that way.

Alejandro Varela 31:34

My my DMs have blown up with this book in ways that the first two didn't, and not just people coming out to me as Polly, or telling me that they are in so much pain because so and so left them a few months ago. Thank you for this salve that you it's also like my daughter was just diagnosed with OCD, and this is the first time I've seen this written about. Can you recommend some resources for me? So it's been kind of and that maybe is the public health part of me, but also I just want to always be careful. I read the heck out of the OCD information out there. I talked to lots of people, including therapists. I didn't want to misrepresent this, but I felt like it was important, yeah, lots of people. And I'm like, Yeah, because if it's the 10th most common, so then a lot of us are walking around with this.

Traci Thomas 32:22

Okay, I want to talk about the DM things you you and I talked about it briefly, like just at a cocktail party, and I heard you talk about it briefly at the festival. But I'm curious about like you Alejandro, just a regular, degular guy who writes books. You're getting these DMS about your work. I guess the question is less about like, what's in the DMS, and more about, how do, how does receiving them make you feel about your work? Like, what is the relationship between you? Like, the triangle you the DM, and then the book itself.

Alejandro Varela 32:59

The DM started, you know, started with the first book, and they were always really heartfelt. I feel like you wrote about my life as a queer kid, as a brown kid, as a suburban kid, so on and so forth. And I didn't, I don't sit down and think, Oh, I I have to write for people who might connect with me. I think I'm writing about some pretty universal stuff that hasn't gotten a lot of attention, maybe deserves more attention, and so that's out there, but it does reinforce my desire to be respectful about things. In my first book, I write a fair bit about schizophrenia, and I knew I did not want to get that wrong. I'm like, let me not hold up a system like already schizophrenia is seen as such, like a villainous, dangerous illness. Yeah, you should be afraid, afraid, afraid. And I'm like, there are humans, you know, dealing with this every day. And when I started getting DMS from people with mental illness, they didn't some people were very honest about schizophrenia, someone in their family, I thought, okay, I cannot let my guard down on this. So if I ever write about mental illness again or health in general, I got to do the work and really think about, how am I representing humans? And so the DMS in that way, they're really heartening. They personally, they are validating. They make me think that I'm I've chosen a path, a career, a job where I'm doing more good than harm, and that's, you know, that's all I ever want. This is going to sound like humble bragging, but it's, it was just nice, and I hadn't had that experience before with this new book. For the first six weeks, every single day, like clockwork, I had two or three DMS from someone saying, I just finished this. You understand. You understand. You understand. Thank you. Thank you. Thank you. I had another one being like, my favorite was people also shared their George Michael stories. Because there's, as you know, there's a George Michael bit, which is completely fabricated. And they were like, I also met George Michael and I didn't, but I just left it there. I was just like, Thank you for lettin me know that's really great, but, yeah, it's quite heartening, heartening, and it makes me want to keep writing. I was going to anyway for the record, but it actually it's like more impulse

Traci Thomas 35:09

So people don't need to DM you to be like, keep writing. Okay, you have a background in public health, which shows up in this book, and it sounds like maybe shows up in your other books. Can you just talk about that? What was it about, about public health that you wanted, why you wanted to go into it? Was it hard to leave, to become like a full time authory guy? What? What's the what's the deal there?

Alejandro Varela 35:34

I stumbled into public health before I went into meet with the director of a program there at the University of Washington in Seattle. I don't think, yeah, I had never I wanted to be a lawyer. I was thought for grad school, I'll go to law school, and I was just sort of working, but we moved to Seattle in search of a job for my partner at the time and and so I just went to the school, and I said, let me see what you got. And when they started explaining to me what this program was in the School of Public Health, I thought, these are all my interests. This is everything.

Traci Thomas 36:11

What was the program?

Alejandro Varela 36:12

It was called the community oriented Public Health Practice Program. And effectively, it was training public health workers to go right into the field and do community based work. And I was most interested in the work that met people where they were at and that made everyone you partnered with was an equal to you. So you'd know there were no research subjects. Theoretically, it was like you went into the field, sure, you had a grant from the state, and it wanted to focus on diabetes. And so then you go to stakeholders in a community, and you say, hey, we want to work on diabetes. What are you? And you ask them, What are your biggest concerns? And if they say, you know, police profiling and bad schools and food deserts, then you have to find a way to make that the focus of the work that you're doing. Because if you're going to impose it's just soft imperialism, right? It's not like working on diabetes is bad, but it's not getting at the root causes. It doesn't get at the root causes. So public health, to me, was like, Oh, it was the matrix. These are, we are a series of experiences, duh, right? And they determine our actions, dealing with the actions and not the circumstances in which we live in that lead to those actions is such a fool's errand. It is a conveyor belt, and you can never leave the conveyor belt. So that's what most interests me. In public, I was like, This is who I am, and I believe in some ways, having been the child of immigrants who spoke English as a second language, and who moved into a community where we were not like the others. I was training to be a public health worker. All along, I didn't realize it. I was doing everything in my power to interpret culture and ideas and language to keep my family healthy and safe. And so it lent itself, quite naturally, to then studying public health. And then my passion just became around hierarchies and health. And so I wasn't doing that. I was doing cancer research, and then HIV AIDS, curriculum writing, and then teaching. And the teaching I always I realized so much of it, the communication that I was most interested in was writing either op eds or policy papers or research studies. And then I realized that telling people to wear a condom is so much easier than telling them to collapse a hierarchy. How do you do that? How do you operationalize that? And then I got to thinking about what media says with me, song, TV and books. I thought, I want to communicate these ideas in a way that will stay with people and will reach more people. So that's where that's where the writing came from. That's where it became narrative and and storytelling. And I often tell in public health spaces, I I will say I consider myself a public health worker, and my medium is fiction.

Traci Thomas 38:56

That's so cool. Can you talk about what a hierarchy of health is?

Alejandro Varela 39:01

So what we know is that when you start to separate people by status, by differences, so in a country like the United States, which is governed by capitalism, it is quite beneficial to people who hold the most power to separate us, because if we're united, then we ask for more, and then profits are less. I mean, the point of capital is, no one's gonna argue with that, is profit. Argue with that, is profit increase. And so for a long time, for the history of this country and the world, we have been stratified by differences. So our race differences, our gender differences, our stat our ability differences, all of those differences which should be celebrated and beautiful, in fact, or become barriers. And what we know now is that when people feel that stress of difference, what does that look like if you live in a community where you feel like you're being judged, where you feel like someone doesn't trust you, or you feel like you're being looked at in a strange way? What. Where the cops might be coming after you, where it every moment you are reminded that you are either unwelcome, different, untrusted, all of those things. What happens is that this the measure for stress increases. Cortisol is neurochemical in your body. That neurochemical is so helpful, Traci, if you're trying to outrun a lion in the Savannah, okay, right? It's incredibly stressed. It's incredibly useful. If you're about to give a speech, or about to give birth, all of these things, it's fine, because it's temporary when that when those levels stay elevated every single day of your life, the wear and tear in your body increases, and then life expectancy decreases. And so that's why in the United States, we have life expectancy lower than what they have in Japan, slight, almost the same or lower than what they have in Cuba, in every other country where they have figured these sorts of things out. But we keep separating ourselves by differences, and it's quite obvious, because if you're up there in the hierarchy, and I'm down here, right? Like we know in race, White's up here, black and indigenous down here, yeah, and then everyone else falls into the middle in some way, shape or form, if you need a visual, if you're up there and I'm down here, we can't really connect, right? We can have moments of connection. There can be Hollywood movies about those connections. But actually, in terms of entire communities, we are kept apart from each other. Make it a gender hierarchy. Make it a sexual, sexual identity hierarchy. We can say we're all like united in some moments, and we can have communities where micro communities, but by and large, the socio economic data bears out, life expectancy, illness, earning potential, all of that shows that we are actually quite different, and as long as we're different, then we have higher levels of cortisol in our body. The 1% in this country has worse health outcomes in the 1% in all the other wealthy countries in the world, because it affects everyone in the higher everybody. The difference is the 1% can get a massage so they'll live longer, right?

Traci Thomas 42:03

Okay, but can I ask you this, then, if you see yourself as like a public health worker and your medium is is fiction or as books, how do you make sure that what you're writing in your books doesn't come across as like preachy or like too moral, or like that you're trying to do something like in the way that, like, one of my favorite songs we are the world is just so cheesy, because it's like a public health song, right? So like, how do you balance? I just, I just love the documentary that they did about how the song got made. So now I'm like, I've been listening to the song a lot this year, which is so embarrassing. And I love Lionel Richie, but how do you make sure that you're not doing that? Because I feel like I could see Alejandro, the public health person, like, I could see that the person who wrote this book thought, has thought a lot about these ideas and these concepts. Like, there's a lot of stuff about HIV and AIDS and like, it comes up a lot in the work, but I never felt like you were trying to tell me some piece of information that I needed to agree with you on. Well, a little bit because it's persuasive, because it's emails, but like it didn't feel like it didn't feel preachy. It didn't feel like you were moralizing to me in a way that felt out of character for the book. Is how I guess you should say it.

Alejandro Varela 43:22

Well, I'm very happy to hear that, but it is a that is a challenge I put on myself all the time. And I would say that the first draft of every piece of writing we ever had has been too preachy. Because I've been finding, trying to find my tone. That's I'm getting better at that with each work, to be honest, two, there are two things there. I try to undercut a lot of that with humor. I'm still trying to tell a story like I am. Maybe it's because I grew up in a stressful household, and you don't want to upset people in a stressful household. You want everyone to be happy all the time. And so when I'm writing, I'm thinking of a room I'm not like I want everyone to love this, but I am thinking I want everyone to enjoy what I'm writing. You know, I do want there to be pleasure from the work. I want people to like the sentences. I want people to be moved. I want people to laugh. I want all of that. And so

Traci Thomas 44:15

Wait, can I ask? Just insert a quick question, Who are you thinking of that's in that room? Are you thinking about who is in the room specifically?

Alejandro Varela 44:25

I guess I'd be lying if I said no, but I try not to make it that specific. I think sometimes I do think specifically around marginalized communities or oppressed communities. I'm thinking, I don't what, where are my I don't know if this phrase is correct, but where are my blind spots here? What will I write here that in some way will reinforce an idea or it just won't come across? That's what I that is kind of an edit mentally for myself. I'm just like, Wait a second. Is this three dimensional? Or did I just recreate a trope that I've hated for, you know, the last 40 years. I'm usually okay on that front, but it is a concern. So in that way, I guess I'm thinking, If so and so read this book, would they be like ale No man, you just, you just did us wrong, right? Like that. That is a feeling that crosses my mind. But generally, I'm just thinking what I think every time I'm at a party, I want the room to I want the circle I'm in to smile, right? Like, I want you to enjoy my company. And so I think I want you to enjoy the words that I'm putting on the paper. And so that's, that's part of it is, it is a desire to do that. So then it does become about like reading the room in a literary way, this is a lot, but how do I make this a lot funny, so interesting that that it disarms you, so that even though you are being preached to, it's like, well, this is kind of fascinating. So I kind of want to know this. And then there is a whole streak in me when I'm like, Oh, do I cut this? Do I keep this? Do I keep this? And I'm like, You know what, if I only live to be 79 I'm 46 as of Saturday. I need to get this thought out there. And so it may turn off a bunch of people when they read that thought, but I bet you the people, there are some people to be activated by that thought. And so I just need to, I need to put this out in the world. And and then I have activated.

Traci Thomas 46:23

I was activated by them. I was I was like, Ooh, I love this. I love the way that this guy thinks, you know, our narrator.

Alejandro Varela 46:30

And then I have, like, people like Ibrahim Ahmed, my editor at Viking and Robert Guinsler, my agent at Sterling. They are first readers. And I think I trust them. If I was really messing up here, they would say, Hey, dude, cut it back. You know, this is not you're going to lose more audience than you think.

Traci Thomas 46:51

Do you ever think, Okay, this is something, this is like, not really about you, but it could be, I think it might be one day, which is like, do you ever think about how people have these editors and agents early in their career, who they really like, who they really trust, and then as the people get older and more successful, they still have the same team. But the work is worse, because those people no longer feel like they can tell them like, hey, this sucks. Do you ever worry about that?

Alejandro Varela 47:12

I have not worried about that on myself, because I am I edit the heck. I wrote this book in five weeks. Oh, the first draft, and I edited. I edited for a year and a half, okay? And so,

Traci Thomas 47:27

so you throw everything on the page as quick as you can, try to just get the bones, get the story, and then you're gonna go back and like, TV like, and how many edits is that? Do you edit all the way through? Or do you do, like, I'm gonna get this scene right, or I'm going to get this email right, and then go on to the next one.

Alejandro Varela 47:44

I edit all the way through painstakingly. I might. Part of my new practice with this book is i i started different places in the book and then circle back, okay, it's very easy to get caught up editing the first chapter in the first paragraph forever, like, like the first child, and then the first child is great. And then you get to the middle child, and you're like, what I forgot about? And then by the end, you're like, you just threw the diaper at the child. You didn't even right? And so I and you feel that when you're reading people's books, how many times have I talked to friends who like, it's spectacular, then I call them back. I'm like, how so and so. Oh, it dropped off in the middle, and by the end, I wasn't so interested. And you realize, yeah, that's because every time you got up to go to the bathroom, you went back and edited from the beginning, yeah, and so by the end, you edited a lot less. So I make sure that process to edit for a long time. But to go back to your original question, I have read work by people who I adore and who's or whose work I adored, and then I got into a place where I'm like, Oh, they let you have way, like people just stop giving you opinions.

Traci Thomas 48:48

They're not telling you the truth. I don't know. How could you have the same team who did that first book? And now on your ninth book, it is this, I'm just like you, they're lying to you because you're a cash cow for them or whatever. That's my nightmare as a person who makes things in the world. It is my nightmare that that someone who I trust in the beginning not not to put doubt in your head about your lovely team. It's just something that I think about, especially this time of year, because it's like book award season and the lists and everything. And sometimes I'll see things on these lists, and I'm like, that wasn't even good. They're just famous, you know? And I'm just like, I hate it here. This is really just me venting.

Alejandro Varela 49:28

I think, no, I think I know exactly what you mean, and this does happen, yeah, but I, my hope is that that will never happen

Traci Thomas 49:37

mine too well, I'll make sure to we make sure to clip this section and send it to your team so they know. We don't want them to be nice to you. Even when you become a star of the literary world, household name, we're going to be like Ibrahim. Stick it to him. Yeah.

Alejandro Varela 49:54

Let's also pin some hopes on cash cow. What did you call it? I want one cash cow.

Traci Thomas 50:02

No, you You are the cash cow, because anything you write makes money. Yeah, you are the cash cow, eventually, you become that. I don't want to name names, but there are some people whose books have come out this year that are cash cows, and they're bad books. But let me ask you this, besides the obsessive editing that goes on for years and years. How do you like to write? How many hours a day, how often music or no snacks or beverages? Are you in your house? Are you at a coffee shop? Do you have rituals? Give me the scene.

Alejandro Varela 50:34

There's no better place to write for me than on the Long Island Railroad heading from New York City into Long Island either visit my parents or to go to Fire Island or to take a trip. Nothing better. Same goes with Amtrak if I have to, when there's no worse place for me to write than a plane, because in a on a plane, I'm too nervous and I've either had the assistance of a medication or a beverage, so then I'm not the same person. But I I require a certain amount of quiet, and so sometimes I'll just put white noise on my headphones. Sometimes I can't listen to new music. If it's new, I'm too interested in what I'm listening to, yeah, so I will listen to sometimes, if I'm on a roll, I will just hit repeat on a song, and I can just listen to it for like an hour on the train.

Traci Thomas 51:28

Okay, that does the song have words, or is it like classical or instrumental?

Alejandro Varela 51:32

Oh, it has words. It has words. I wish I could give you an example right now of one, there's a I there's a new song by Jane Handcock featuring Anderson paak called stare at me. It's a jam. It's so, so fun. The Grammys dropped the ball big time. I had not heard of Jane Handcock before, but Jane, you killed it.

Traci Thomas 52:15

We love you big fans over here.

Alejandro Varela 52:18

Anyway, so music, when I wrote the first book, I needed to get into the mindset of that era that takes place in the late 90s. I made a list of 170 or 80 songs from 1994-1997 and I listened to those on loop for the 13 weeks that I wrote that book, or 12, whatever it was. And I Yeah, so sometimes I need to do exactly that for for time travel.

Traci Thomas 52:45

Yeah. What about snacks and beverages?

Alejandro Varela 52:48

Just water. I can't really be, you know, that's a lie. I have been known to especially when I'm vacation or when I'm taking, like, a auto retreat. I'll just be like, I'm gonna leave town for the weekend and write, if I can do that. It's happened so infrequently, but I will treat myself to a martini in the afternoon, and then I will go home and write really well for a couple of hours or a few hours, and then I'll go out, yeah, and have dinner that is nothing more romantic to me than sitting at a restaurant by yourself, and really at the bar by yourself and having Yeah, whatever it is, I love that feeling

Traci Thomas 53:26

No snacks you are clearly not a snacker, is what I'm hearing. Not great for our relationship, to be honest.

Alejandro Varela 53:33

I'm sure I have snack what ends up happening is that when I'm on a roll, I don't take care of myself. I will hold in having to pee. I will not get up to get water. I will not and so that is, that's really bad, yeah, but, but, you know what? When I go to the library and I will fill up my bag, I have a bag of, like, roasted peas here and some dried salmon, I'm on a protein kick right now.

Traci Thomas 53:58

Oh, my God, you're so healthy. I want to die. I was hoping you were going to be like, I'll throw in like, m&ms

Alejandro Varela 54:05

I wish I could remember that brand, these delicious m&m-like candies around now that are gluten and dairy free

Traci Thomas 54:13

Are you also gluten and dairy free like our narrator?

Alejandro Varela 54:16

yeah, I'm giving some love to those communities in my books.

Traci Thomas 54:19

Yes, congrats to you, communities. I'm so glad I'm not there really ruined my life. I'm an extremely picky eater, and so, like, there's basically a lot of things I just don't eat, and then I have a few allergies, so like, dairy free not an option for me. That's like, how I get the majority of my protein. It's like, basically, Greek yogurt is my is my entire source of protein.

Alejandro Varela 54:43

I'm the exact opposite. I have. My superpower was that I could eat absolutely everything you put it in front of me. I will eat whatever you make. I will. I won't bat an eye lash. But then I turned 40, and gluten and dairy became my enemies.

Traci Thomas 54:58

Oh my God. I turn 40 next year. If that happens to me, God, I can't, please don't that will be the heartbreak of my life. Yeah, that will be, that will be the thing that finally gets me to write a heartbreak novel. Okay, we're basically out of time, but I just have like, two more questions for you. One is that for people who love Middle Spoon, what are some other books you might recommend to them that are in conversation with what you've created?

Alejandro Varela 55:28

I will say that Natalia Ginsburg is a writer, Italian writer, who I discovered not that long ago. And I really love her voice. I don't I think it's maybe praising myself too much to say we're in conversation, but I eavesdrop on her conversations, let's say. So, Natalia Ginsberg's work is just fabulous. Thomas Bernhardt and his work, whether it's Wittgenstein's Nephew or Loser or Extinction, these are really curmudgeonly books that with exhaustive narrators or exhausting, sorry, exhausting narrators, but that I learned so much from. And so I really love it, and I feel the same way about Sebold. WG Sebold. I'm trying to think of someone maybe more contemporary that would that, I would say, but nothing comes to mind immediately.

Traci Thomas 56:27

That's okay. We love a backlist moment. Okay. Last question for you, if you could have one person dead or alive read this book, who would you want it to be?

Alejandro Varela 56:35

Hey, Terry Gross. Give me some love.

Traci Thomas 56:37

Oh, Terry, sure. You've never been you've never done Terry Gross?

Alejandro Varela 56:46

I've never been on NPR. I thought it was NPR ready.

Traci Thomas 56:49

I think you are too. See, this is how we're gonna get you to be a cash cow. That's the first step, right? You got to work your way up. And then you get to NPR. Then it starts trickling in. Then you write another that you know, and then all of a sudden, look at you. You could write about anything you want, and it could suck, and you could sell a million copies and be on the best seller list every day, and then I have to read it, and then I have to be annoyed, because I'll be like I used to like his stuff, but not so much anymore. But we don't want that for you. We want a prolifically good cash cow.

Alejandro Varela 57:20

I will, can I can I give it someone who's dead? My friend Gene, who died in very old age, but a couple years after the pandemic started, unrelated to the pandemic. He was my biggest champion. I love, adore this man so much, and so I wish he could have read all of my books. He did get to read the first one. So I'm happy about that

Traci Thomas 57:41

Oh, I love that. Okay, people of the world, you can get this beautiful book, which also happens to be in my favorite color combination, pink and red. It's my go to. Everything I own is pink and red, from my water bottle to my Kindle case. So obviously that was a draw for me too. You can get middle spoon. Wherever you get your books, you can listen to the audiobook. I listen to some of it. It's absolutely delightful. It's such a voicey novel, obviously, since it's epistolary and it's written in emails, it's all one voice. So it's really great on audio. Alejandro, thank you so much for being here. This was wonderful.

Alejandro Varela 58:18

Thank you, Traci. I really appreciate this. This was a blast.

Traci Thomas 58:21

And everyone else, we will see you in the stacks. All right, y'all that does it for us today. Thank you to Alejandro for joining the show, and thank you to Magdalena Denise for helping to make this episode possible. Our book club pick for December is Friday Night Lights a town a team and a dream by HG Bissinger, which we will discuss with Joel Anderson on Wednesday, December 31 if you love the stacks and you want inside access to it, head to patreon.com/the stacks to join the stacks. Pack and check out our newsletter at Traci Thomas dot sub stack.com make sure you're subscribed to the stacks. Wherever you listen to your podcasts, and if you're listening through Apple podcasts or Spotify, please leave us a rating and a review for more from the stacks. Follow us on social media at the stacks pod, on Instagram, threads and Tiktok, and now we're also on YouTube, and you can check out our website at the stacks podcast.com this episode of the stacks was edited by Christian Duenas, with production assistance from Sahara Clement. Our graphic designer is Robin mccreight, and our theme music is from Tagirajus. The Stacks is created and produced by me. Traci Thomas.