Ep. 394 Wildfires Are a Systemic Issue with Jordan Thomas

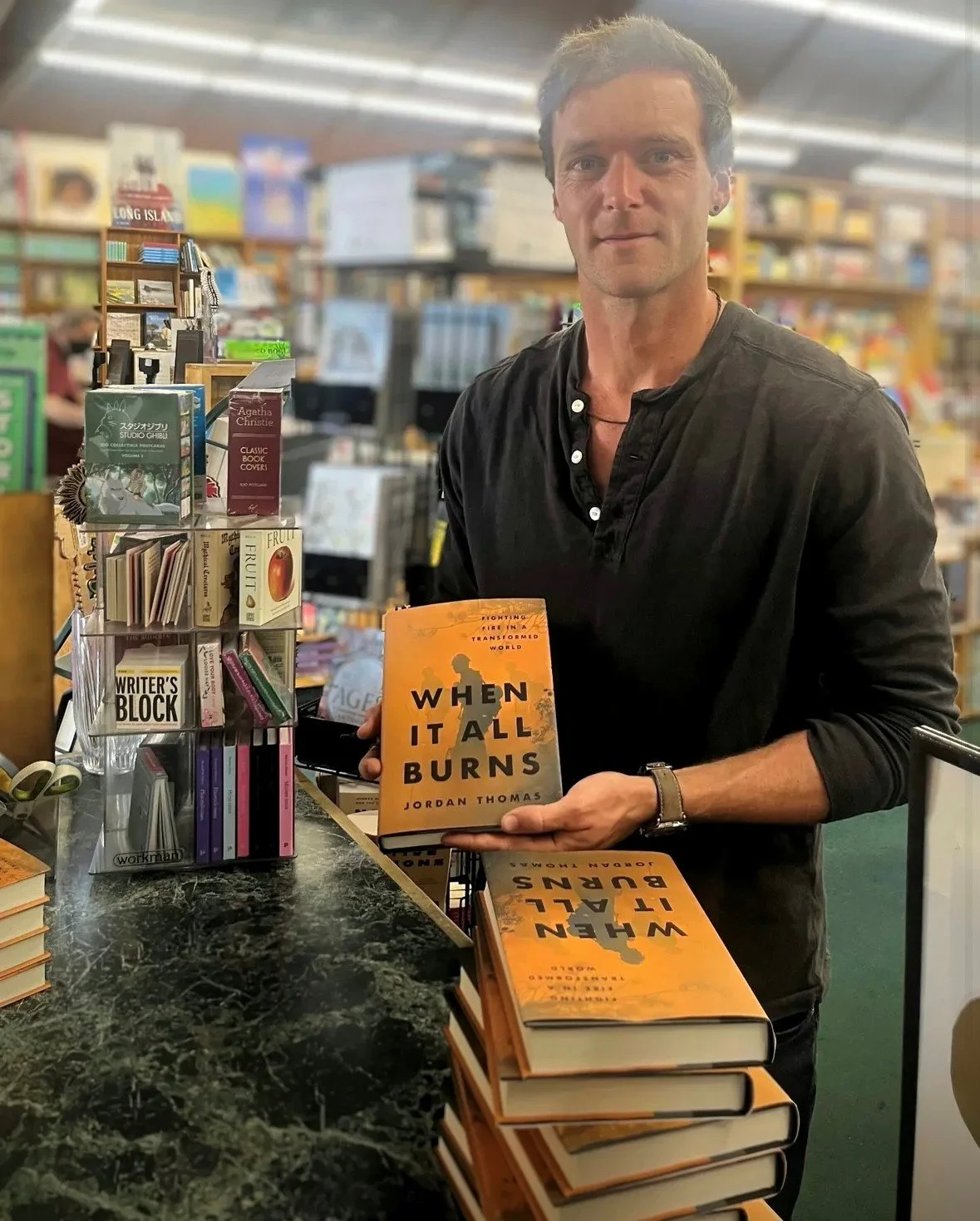

Today on The Stacks, we are joined by anthropologist and former wildland firefighter Jordan Thomas. He’s here to discuss his first book, When It All Burns: Fighting Fire in a Transformed World, a gripping exploration of his experience battling a brutal, six-month fire season with the Los Padres Hotshots, an elite force of wildland firefighters. We discuss Jordan’s transition from firefighter to author, what the general public gets wrong about wildfires, and the connection between fires, climate change, and Republican politics.

The Stacks Book Club pick for October is Frankenstein by Mary Shelley. We will discuss the book on Wednesday, October 29th, with our guest Angela Flournoy.

LISTEN NOW

Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Google Podcasts | Overcast | Stitcher | Transcript

Everything we talk about on today’s episode can be found below in the show notes and on Bookshop.org and Amazon.

When It All Burns by Jordan Thomas

“Ep. 341 Am I Supposed to Be Here With Jason De León” (The Stacks)

Soldiers and Kings by Jason De León

Braiding Sweetgrass by Robin Wall Kimmerer

“Ep. 386 Braiding Sweetgrass by Robin Wall Kimmerer — The Stacks Book Club” (The Stacks)

Tending the Wild by M. Kat Anderson

The Storm Is Here by Luke Mogelson

The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle by Haruki Murakami

Fire Weather by John Vaillant

Hotshot by Rivers Selby

Paradise by Lizzie Johnson

The Lost Bus (Netflix)

When It All Burns (audiobook)

To support The Stacks and find out more from this week’s sponsors, click here.

Connect with Jordan: Instagram | Website

Connect with The Stacks: Instagram | Threads | Shop | Patreon | Goodreads | Substack | Youtube | Subscribe

To contribute to The Stacks, join The Stacks Pack, and get exclusive perks, check out our Patreon page. If you prefer to support the show with a one time contribution go to paypal.me/thestackspod.

The Stacks participates in affiliate programs. We receive a small commission when products are purchased through links on this website.

TRANSCRIPT

*Due to the nature of podcast advertising, these timestamps are not 100% accurate and will vary.

Jordan Thomas 0:00

It's really hard to innovate your way out of systemic issues. These massive wildfires we're seeing are manifestations of systemic issues. So what does it take to get our landscapes back to a point where they'll be resilient against climate change? It means investing in people, the people who are working in our forests, and I think that that's what's often missed, because people like hot shots, and people equipped to give the land the kinds of fire they need, they don't look like technology because they're rough and they're sweaty and they work outside. So I'm really trying to emphasize that these are some of the most high tech solutions we have, and they're people, and we should be pouring money into these people to support them so they can do what they need to do to get our lands back to how they should be.

Traci Thomas 0:49

Welcome to The Stacks a podcast about books and the people who read them. I'm your host, Traci Thomas, and today I am joined by wildland firefighter and anthropologist Jordan Thomas to discuss his debut book, When It All Burns: Fighting Fire in a Transformed World. This book was long listed for the National Book Award. It's a gripping tale where Jordan recounts his experiences battling a brutal six month fire season as part of the Los Padres Hot Shots, an elite force of wildland firefighters. The book is a blend of memoir, anthropological research, and historical investigation, and he and I talked today about the systems at play, from climate change to mental health to colonialism, that has led to the increase of these mega wildfires. As a reminder, our book club pick for October is Frankenstein by Mary Shelley. We will be discussing the book on Wednesday, October 29 with Angela Flournoy as our guest. Everything we talked about on each episode of The Stacks is linked in our show notes. And if you like this podcast, if you want more bookish content, more bookish community, consider joining The Stacks Pack on Patreon and subscribing to my newsletter. Each place offers different perks, like community conversation, virtual book clubs, hot takes on pop culture and bonus episodes, plus your support makes it possible for me to make this show every single week. To join go to patreon.com/thestacks, to be a part of The Stacks Pack and check out my newsletter at TraciThomas.substack.com. All right, now it's time for my conversation with Jordan Thomas.

Alright, everybody. I'm so excited. I am joined today by National Book Award long listed author Jordan Thomas, whose brand new book, When It All Burns, is out in the world now, Jordan, I'm so excited. Welcome to the stacks.

Jordan Thomas 2:36

Thanks for having me on Traci.

Traci Thomas 2:38

I'm thrilled. So first and foremost, we are not related, though we are both Thomases, at least, to my knowledge.

Jordan Thomas 2:46

We could be, you never know.

Traci Thomas 2:48

Where did you grow up?

Jordan Thomas 2:50

I grew up in a small town outside Kansas City.

Traci Thomas 2:53

I don't have any Kansas City relatives, to my knowledge, but you know, there's many of us, but you wrote this book. You're an anthropologist. You wrote this book. You became a hot shot, a firefighter, like the top tier firefighters. Can you just tell folks a little bit in like 30 seconds or so what the book is about?

Jordan Thomas 3:14

The book is about how wildfires have gotten so big and so violent in California but also around the world, and how people navigate them in a really physical level, on their edges, how people survive on the edges of these extreme environmental events, and what that can tell the rest of us about how to navigate the climate crisis.

Traci Thomas 3:32

So I live in LA and I'm from Oakland, so I have many stories about, you know, I feel like I've lived this sort of California Fire thing, which, you know, reading your book, I'm sure, for everyone, it feels really impactful. But to read it this year, after the fires we had down here, you know, in January, it just, it's like, I mean, it's a hard book to read because it just feels so like these fires are starting to feel so inevitable because of what's going on. And so I'm wondering, like, what made you want to write this book now? Why did you feel like we had to have this conversation in this moment?

Jordan Thomas 4:15

You know, I wrote the book because I had the opportunity to, okay, I had the opportunity to write the book, actually, after I finished the season on the hot shots. And as I was finishing the season, I was feeling like there was just so much that I had witnessed and participated in, in terms of the changes happening on our planet and how people are navigating them. And I had this feeling like it was all pent up, and I just had to get it out. But I didn't have any where to put it until I had the opportunity to write this book, and then I just poured myself into that project.

Traci Thomas 4:50

So in the author's note, sort of at the end of the book, you say that you didn't know you were going to write the book when you joined the hot. Shots. So why did you join the hot shots? Because you're an anthropologist, like you were studying in in the UK. You're like a, you know, you're like a smarty, a smarty guy, like it wasn't like you always wanted to be a firefighter. So what made you want to join the hot shots? And then, what did you think you were doing by joining the hot shots, if you weren't writing the book.

Jordan Thomas 5:22

you know, I started fighting fires sort of serendipitously when I moved to California, because I had about 10 months between academic jobs, and I had a little bit of research interest in fire, but more it was just a way for me to stay outside and get involved in in California and get to understand California's people and places, because I moved there right after the Thomas fire happened in Santa Barbara, which is where I lived, and that was, at the time, the largest fire that had ever occurred in California. And everybody had a story about the fire, or a fire, something that I lost, or somebody they had lost. So I got involved with fighting fire in that way, and realized how little I knew I expected to be fighting with fires with a hose and with Dalmatians and fire engines. Instead, I was handed a chainsaw and told to race up a mountain and through that, you know, my curiosity was just sparked. It was like it was like opening the wardrobe to Narnia and seeing this whole other world unfolding, and the hot shots are as deep as you get into it. So when I after a couple years on that beginner crew, once I got the offer to join the hot shots, I was like, I can't say no to this, because these are the people who get us closer than anyone else to the largest fires that have ever been recorded in California. And that's just not something you say no to for me, at least, because of the curiosity and the the the opportunity to to witness these events and and get so close to them, with the people, and learn from the people who survive on their edges. And so I did that. So I joined the hot shots. But I'm also an anthropologist, and I move through the world with an anthropologist mind, and I've been a sort of obsessive note taker since I was a kid. So everything sort of converged in a way that that wasn't, that wasn't necessarily intended or planned out. You'd, I think I'd have to be some sort of sociopathic genius to, you know, like eight years ago, say, Okay, I'm going to move to California, join the most elite hotshot crew in the world, land a deal with this incredible publisher, and write a book out of it. You know

Traci Thomas 7:31

I feel like a lot of anthropologists do have some sort of vision of like, what they want to, like, write about or, or how like that they want to embed with people, right? Like, I mean, last year we had Jason de Leon on, and he wrote the book about soldiers and kings, and it was about, like, you know, people trafficking across the border. And so he spent years, you know, embedded with them. And I feel like he went in knowing it wasn't like he, you know. So I feel like you don't have to be like a psych sociopath or like an evil genius. I feel like you could have just said, like, I want to write about firefighters, and I would allow it is all, yeah.

Jordan Thomas 8:09

I think the thing was that I had no no means or connections to literary industry. I had no I see. So as I was moving through this world, I was always thinking, Okay, how would I write about this? And I've, like, I've researched this area of California and how the logging industry has transformed the forest there, and how that influences fires. And now I'm on the edges of these fires here, which is, it's a million acre fire, which has never happened before. Like, how would I organize that and write about it? But, like, the difference was, I just, I had no it felt kind of like wanting to be an astronaut or something like, great, you want to go to space, but, like, I just had no connections to that world

Traci Thomas 8:46

I see. So you sort of had an idea, like, this could be a book. You just didn't have the means to be like, how do I make this a book? Or, like, the connections to make it a book, and what? How did that piece of it come about? Did Riverhead reach out to you? Did you decide to write a proposal like, what was that process?

Jordan Thomas 9:05

My second year on a fighting fires, a friend of mine, started a little magazine, and I just sent her a Facebook message asking if she wanted a piece about fires for the magazine. So I mostly wrote about the historical factors of wildfires at that time and but that just it ended up being the at the time, again, the largest fire season in California's history. So the article made somewhat of a splash. And then a year later, on the very last day that I was a hot shot, I started getting emails from a couple different literary agents in New York, and I just happened to be heading out to the area at the time for an anthropology conference. So I was able to go and meet with some different agents. And the one I met with, who I ended up working with, we there was just like fireworks when we met. It was like artistic visions completely aligned, yeah, and it all moved from there.

Traci Thomas 9:57

okay, I see, I love it clearly this. Book is like a fire book. It's about fighting fires. It's about the landscapes. It's about the history. And you have, you went and you embedded, right? And you became, you became one. You know, maybe not intentionally to write a book, but that's what ended up happening. Is there another career or profession or industry that you're like, I would do this again in that space, like, are you thinking about what could be next?

Jordan Thomas 10:25

You know, Traci, it feels like such a privilege now to be a writer and to be in the writing world, and to be able to enter a project knowing that I'm going to write a book about it and be intentional about it in this way. Because, yeah, there's, there's a I'm actually trying to form a project right now, and I probably shouldn't talk about it

Traci Thomas 10:44

You know I like to break news, I'm such a hard-hitting journalist.

Jordan Thomas 10:49

Yeah, I am. Yeah, I'm about to dive deep into another group of people and spend a couple years doing something will lead to, well, hopefully lead to another book.

Traci Thomas 10:57

Okay, can I ask you about whenever I talk to anthropologists who do this. I'm always so curious about, sort of, like, the ethics of the thing, especially, like this first one, you weren't sure it was going to be a book. You thought this would be, like in the author's note, you talk about, you know, I, I thought this would be a cool thing. So I knew I was in the middle of this moment, and so I took obsessive notes. And you talk about like, I took notes on paper, and then when I couldn't do that, I took it on my phone, and when my phone got too hot, I used, like, memory techniques to remember what was going on, and then I would go back, and I took 1000s of pages of notes and all this stuff. But now, as you're leaning to go in knowing, does that change anything like ethically for you? As an anthropologist, I know journalists have sort of a different code of ethics, so I'm wondering how you think about it, knowing going in.

Jordan Thomas 11:47

You know, I think there's a couple different levels of ethics and how people navigate. And there's the institutional ethics, which often I think serves more as like legal cover to be able to write what you want. And then I think that there's the real interpersonal ethics, which is, how do you relate to the people you're working with, and are you speaking for them, or are you using them to tell a story? And what is the purpose of what you're writing? And it was these questions that really just was kept me up at night while I was writing this book, and was a source of a lot of thought, a lot of angst and a lot of conversations with the communities of people I was writing about, which is what I think is important to go back to. And I think just working to make sure you're representing people in the way that they want to be represented, questioning why you're representing them in this way, and just trying to not do people any harm. So for me, it was a matter of going back and talking to people to make sure that they were okay being in the book, yeah, and if they were okay with me using their names in the book, and if I had anything critical to say about them, making them very difficult to identify. And this new project, you know, I think it'll be a bit different, because it won't be like backtracking and making sure everything's ethical retrospectively or retroactively. It'll be a matter of going in and people bringing me into a world and showing me the world intentionally, with me as an identity, as an author, while as a hot shot. I was first and foremost a hot shot and a friend, and then later on, I became an anthropologist and a writer, writing about the times when we were hot shots and friends together.

Traci Thomas 13:26

Yeah, yeah. You said it sometimes the hard the balance of, like, Are you, are you letting them tell the story, or are you sort of using them in a different way? How do you know when, when you're doing it right? Like, is there something that it it clicks for you, like, because you said kept you up at night. So what was, what was the thing? Like, can you give us an example of a time when you weren't sure if it worked or not, or, like, what would keep you up?

Jordan Thomas 13:53

Yeah. So to answer that first question, I think you know when you're doing it right based on the feedback that you get from people.

Traci Thomas 14:04

From the people you're talking about, from your editor, from a friendly reader?

Jordan Thomas 14:07

No, no. I mean feedback from my editor, and from reviews and the New York Times, the L.A. times, like those things are important and they feel good. But I think what was most important to me as the book was coming out was the proximal feedback, starting with my crew members, starting with the people who are in my book, and what they thought about it, and then spiraling out into the broader fire community and the broader community of wildland firefighters, and what did they think about it? And so, for example, I talk a lot about mental health in the book, and those aren't really words that are used in the firefighting community for a variety of reasons, but I try to translate what firefighters do talk about into terms of mental health and compensation and healthcare and stress of the work, and turn that into a narrative that the audience can understand for the purpose of hopefully creating some sort of change to provide better. Or compensation for people in these spaces, as these spaces become more dangerous, but that's always a that is always a risky way of approaching things when you're using terminology that isn't necessarily used within the community. Climate change is another example. Yeah, in my anthropological work, I research the impacts of climate change and how people navigate it, but even as we're on the edge of these massive climate events, these huge manifestations of climate change, it wasn't often spoken about in that way within the community, a while with firefighters. So it was a sort of a balance of representation and how I'm and how I'm framing things and discussing things.

Traci Thomas 15:41

Yeah, yeah, that's really interesting. I do want to come back to both of those, actually those pieces, because they stuck out to me as particularly interesting to discuss. But before we get to that, I'm just curious, on a more broad level, was there anything that surprised you or, like, what was the thing that surprised you most about being a hotshot, living that life like were there things that you went in maybe thinking it was going to be, that it wasn't, or things that you had no idea to expect that you were like, Whoa. This is actually a huge part of my life right now.

Jordan Thomas 16:14

You know, I think I was surprised by how accustomed you get to being really close to fire, yeah, to where you can just be hanging out with fire burning around you, and but that also that's not some sort of I think that what that implies is also this level of knowledge and expertise that people have in these spaces, to where you understand The landscape and the conditions that fire burning so well to where you can exist around fire, really close to it, without with having an intuitive understanding of what it's going to do, so you know if you're in danger or not, right. So that that was surprising when I found myself physically slipping into this mode of being, and I try to use that process of being, I guess, molded into this way of being as as a vehicle for describing the experiences of these of this community of people.

Traci Thomas 17:11

How long did it take you to feel like, comfortable in those situations? Like, obviously me, a person who's terrified of fire. I'm like, I don't even want to be like, 20 miles near a fire. So like, when did you go from kind of being nervous to being like, oh, like, fire's gonna run this direction, like, I'm safe over here, winds blowing this way, whatever.

Jordan Thomas 17:35

It's a spectrum. It's a spectrum. And I from the first time we got called to a fire when my adrenaline just spiked, and everybody and the vehicles were amped, and then it was a tiny, little, tiny, little fire that was basically already out, but it felt like you could see smoke, and it felt so exciting, and all the way up to a point in the Hot Shot crew where the whole forest is burning around us. And I was with one of the squatties that they were just, I didn't know where to go, and he was just leading us out to a space that could be safe and that I wasn't comfortable at that time. I was but the person leading me was very comfortable. So I think, and I will emphasize that I only did one season on a hot shot crew. So it's so I'm still not even nearly as experienced, comfortable as as people who make a career of this. So Aoki, for example, who was the leader of the hotshot crew I was on, he could go through spaces with ease and understanding that very few people could could navigate, because he did have such an embodied understanding of what the land is and what the fire is going to do within that land, yeah. And that's what I'm trying to capture. And I think that creates such a contrast to how people in this profession are treated and compensated, by society, right?

Traci Thomas 18:58

And that even changed, has changed the public perception. I mean, in the book you talk about, there's a scene where it's like, everyone's really like, oh, the hot shots are here. And then later in the book, it's like, ooh, hot shots are here. Like, it's like, a totally different vibe. And I thought that was really interesting, because I think firefighters are our most beloved public servants, right? Like, I feel like they get the most like public. They have the highest like approval rating in the public. That doesn't mean that they're getting paid, what they should be getting paid, or treated, how they should be getting treated. But I feel like, you know, a lot of people don't like police officers. You know, I don't think like ambulance drivers get the same hype. Like, when my kids go past an ambulance, they're not like, ambulance. They're like, that's a fire truck, ambulance, they know the difference, right? I feel like firefighters are really a thing, so I was interested in that, like, sort of shift later in the book. I was like, Oh, the tide's turning on firefighters, wow.

Jordan Thomas 19:55

Well, it's hard because they're there's just different kinds of firefighters, municipal and state firefiighters are treated pretty well, but what I was trying to emphasize in my writing is that hot shots are federal firefighters, and there's this view of the federal government and federal agents that I think is shifting, and is being intentionally shifted for various political reasons, one of which is a fight over public lands in the American West, and who has access to them and who's able to profit from them. And if you're opposing public lands, one of the ways to do that is to oppose compensation for public servants, of which Hot Shots are so hot shots actually aren't technically considered firefighters

Traci Thomas 20:33

You're forest workers, right?

Jordan Thomas 20:36

Forestry technicians.

Traci Thomas 20:37

Forestry technicians. Do you like my official term, forest worker. You're forest worker. What do you think people, non fire related people, just, you know, us regulars. What are we getting wrong about fires? And why are we getting it wrong? Because so much of the book is you explaining this history and sort of the ways that the government and the public opinion has shifted and changed, and much of it has to do with, you know, capitalism and racism and a hatred of indigenous people and their knowledges and technologies. So I'm wondering, like today, in 2025 what's the big thing that we're still getting wrong about fires?

Jordan Thomas 21:25

I think one of the most important things to get right about it is the idea that there are a lot of different kinds of fire, and there are a lot of different kinds of fire that belong in California's landscapes, and so treating fire is a one size fits all category that you have to put out is a big part of the problem, and that's been happening for a couple 100 years now, which has created this really destructive kind of fire. But I mean, California is one of the most Fire Adapted regions on Earth, and each ecosystem needs a particular kind of fire. So I think differentiating between sorts of fire that landscapes need and then what kinds we should be putting out is an incredibly important distinction that we need to make. But then again, there's also the question of, how do you give the land the right kinds of fire? And so what people what I want them to understand in this category, which is, how do we solve the problem? It's that it's really hard to innovate your way out of systemic issues. And all of the problems we like these massive wildfires we're seeing, are manifestations of systemic issues, which I go through in the book, which begins with colonialism and the genocide of California's indigenous people, which open spaces for corporate logging and forestry, which now climate change is blowing up. And so what does it take to get our landscapes back to a point where they'll be resilient against climate change? It means investing in people, the people who are working in our forests, and I think that that's what's often missed, because people like hot shots and people equipped to give the land the kinds of fire they need, they don't look like technology because they're rough and they're sweaty and they work outside, and they're often denigrated by politicians who oppose compensating them as unskilled labor for these reasons. So I'm really trying to emphasize that these are some of the most high tech solutions we have, and they're people, and we should be pouring money into these people to support them so they can do what they need to do to get our lands back to how they should be

Traci Thomas 23:33

Right. Okay, we're going to take a quick break and we're going to come back.

Okay, we're back. I want to stick on this sort of like people as technology idea, because I think, you know, at the beginning of the book, you have another sort of note in the introduction, or maybe it's a different author's note, and it says, you know, you're talking about, sort of your place in this conversation as a white guy, and how, you know, you're dealing with a lot of indigenous technologies and sensibilities and like, is it your place to say this, or how you are, you know, envisioning your place for this. So could you talk about that a little bit? Because it does feel sort of like worth covering.

Jordan Thomas 24:18

Yeah, I found myself in a really complicated situation as a writer, occupying my position in society, as a white man, not even from California, from from Kansas, coming to write about about fires, which doesn't sound on a surface like it would be that complicated. But the more I was digging into the origins of this crisis, the more that I became to understand that it was intertwined with indigenous people's history and the history of European colonialism in the state and then American colonialism in the state for for over 100 years, and that a lot of the solutions being implemented now are being driven by indigenous people. And so as an anthropologist there's a really troubling history of white anthropologists like myself telling the story of indigenous people on their behalf in ways that don't represent them and often perpetuate the very systems that have historically and today worked to take away their sovereignty and and subjugate them and and in their landscapes and their territories, and but at the same time to not tell that story is an act of erasure, which is has its own history and our landscapes, which is pretending like it's wilderness, or like like, like these places were just existing, like Eden, that which Europeans discovered and came to to inhabit, which in reality, these landscapes have been shaped by indigenous people in their fire use for many 1000s of years. Fire was one of the main ways indigenous people in California and across the United States really cultivated landscapes that had enriched biological diversity and were also good to live in for a variety of reasons. So I was kind of caught in this space of not wanting to narrate indigenous people's stories on their behalf, but also not being able to not feel like I could not tell the story because it would be an act of erasure. And there's not an easy way through this. And I'm really don't want to pretend like there is, I'm not going to try to tell the right way to do this, because I think this, these sorts of tensions are ones that I think anybody in this space should sit with and be in conversation about with, with community members and in these spaces and really, so my approach to it was just to have these conversations with people from different tribes that prescribed burns I would go to and talk about how I was representing things. Asked whether it was okay that I'm writing about these things, talk about how I should write about them, and really just try to also draw from indigenous voices and sources and interview indigenous people in these spaces.

Traci Thomas 27:09

Were there any indigenous voices or books or things that you relied on that you think would be like good for people to go to who are listening to this podcast, because this is a book podcast, so they'll read they'll read books. Are there any ones you can point us to?

Jordan Thomas 27:21

Robin Wall Kimmerer's Braiding Sweetgrass.

Traci Thomas 27:26

We did that on our book club in August!

Jordan Thomas 27:28

I saw that you're already, see you're already on top of that. Yeah, and I she has a she has a chapter on fire as well, which I drew from when trying to to include and explain and elevate indigenous experiences and understandings of fire in words that aren't my own. Kat Anderson, I believe it's Kat Anderson has a really good book as well called Tending the Wild, and she's not herself indigenous, But she it's from what I understand, a lot of tribal people consider it to be a very good representation of their relationships with the land. And she, she worked with tribal people across California for many years, so that's a good one as well.

Traci Thomas 28:14

You know, you were a hot shot a few years back. Obviously, you've since taken the time to write the book, and we all know books don't happen overnight. What do you think has changed the most since your time serving as a hot shot? Anything particular that you're like, Whoa, that's different or or worth thinking about this in a new way.

Jordan Thomas 28:35

Oh, well, Donald Trump is president, and Republicans have a or are in control of our government, which has major implications for federal firefighters. So that, that is, that is the major change.

Traci Thomas 28:53

In what way like, what is, I just, you know, I think a lot of people who are not federal employees don't necessarily understand how something like, especially like fighting fires. It's like, Yeah, but they're still gonna put the fires out. It's like, how, how does an administration impact, or this administration impact the work of hot shots?

Jordan Thomas 29:13

Yeah. So this is another really important point, I think, for understanding fires is how much they're influenced by federal politics. So half of California's land is federal land, and around half of the land west of the Mississippi is federal so really the federal government has control over the employment, over forestry, over all of these things that really California doesn't have much control over because Gavin Newsom doesn't controlling what happens with forest management or wildfires on Forest Service or federal land. So what happened with the Trump administration was, I mean, it started with the mass firing of federal employees in the department of government efficiency, quote, unquote, with Elon Musk back in. January, which resulted in an enormous amount of firefighters being laid off, and an enormous amount of the fire mitigation initiatives on federal land being halted, which has sort of backtracked a little bit in recent months, but there's still just so much uncertainty that it's it was already really difficult to staff all of the different Hot Shot crews across California and across the American West. And then these attacks on federal on public servants and federal employees, just made it even more difficult. So we're, we're we're just, we're moving through increasingly intense fire seasons with increasingly less capacity to suppress fires and during the fire season, and even less capacity to mitigate them and make our force more resilient in the offseason, which I know is a little bit bleak.

Traci Thomas 30:52

It's all bleak. It's all bleak. It's just I. Part of reason I'm asking you is because I think, you know, I as a human, as an American, I'm thinking so much about the ways that this administration is impacting all the features of our life and like that, we're able to somehow continue some sort of normalcy, which is like, sort of the design of the decline of the country, right? It's like they want us to still go on dates and, like, read books and have a book podcast, but I as I'm listening to you talk, I'm like, right? This is another thing that is under attack that's crucial.

Jordan Thomas 31:28

And I think it's just goes back to trying to hold the capacity to cut through the smoke and mirrors and be able to view responsibility and hold people accountable for for for things like wildfires, which it's it always when things like the fires in Los Angeles happen and the administration blames California, or as they were in 2021 and as they were in 2020 it's just so important to, I think, keep in mind that this is a matter of a matter that is federal responsibility, and it's the responsibility of the President, of Congress, and we just have to keep that in mind if we want to really get any grasp on the issue. And so there's hope in that too. I think if it's right, if it's political, then theoretically we could change it. We can solve it, change it. You don't sound convinced.

Traci Thomas 32:20

I don't sound convinced. You know, it's dark days, so it's a little harder for me. Sometimes I could be rosier, a little less rosy in October 2025, than maybe if we'd had this conversation in October 2024, or three. But, you know, I do want to talk about the climate, climate stuff, because one of the things that I was totally like mind blown about was when you talked about the Koch brothers and their kind of impact on the climate conversation, and you sort of reminded the reader that you know Bush and Nixon and many Republican presidents had sort of like, done good things for the environment, and that it wasn't until recently, when the Koch brothers decided, like, this isn't good for us financially, that all this climate denying stuff came in. And so I'd love for you just to explain briefly to listeners, if you don't mind, about how come it is targeted at Republican politicians and voters, because that was really like a moment for me.

Jordan Thomas 33:30

You know, that was a really difficult and infuriating couple of days in Big Sur during the heat dome, when it was like 123 degrees, and I was out there fighting the fire and collapsing and watching people collapse and fighting off heat stroke, while also thinking about where this came from. Why is this happening? And I felt like so my earliest memories are in Wichita, Kansas, which is where the Koch brothers are headquartered. It's where they live. Got it? So I and so I've been, I've spent a number of years now tracing the politics of climate change, and the Koch brothers are embedded in this. So in some ways, I felt like this was a good example

Traci Thomas 34:16

This is your story to tell this piece. It's like you're in your backyard.

Jordan Thomas 34:20

Yeah. And I felt like it's a good example of how decoupled violence often is now from the space, from proximity, from physical proximity. It can travel across geographical locations to where decisions that a couple of Kansas billionaires are making are are impacting people and actually physically hurting and in many cases, killing people a long ways away, and this is this feature of the climate crisis is, I think, really real and really profound. And so it is also another dynamic of talking about politics in a way that makes people uncomfortable, because you are saying that this is, that climate denial is a Republican phenomenon, which is a little bit difficult talking about, because people want this, like both sides, back and forth thing and but by I think framing something is maybe you shouldn't talk about it because it's political, then all you have to do if you want something to be not talked about is make it political. And that silences any sort of real discussion. And so with climate denial, it really is a Republican phenomenon that began around the early 1990s when Congress started really converging around the need, a bipartisan need to address climate change in the same way they have all these other environmental problems through time, because climate change is very scientifically understood to be a problem that was going to hurt the economy, hurt the environment, hurt a lot of people, and really just was unnecessary, because there are alternative technologies that could be developed.

Traci Thomas 36:00

And that could be profitable.

Jordan Thomas 36:01

That could be profitable.

Traci Thomas 36:03

That's the piece for me. I'm just like, you could still be making billions and trillions of dollars. It's not like, Oh, if we do use solar power, it's gonna be cheap. Like, it's just like, No, you could still be a freak, freaky capitalist, like, billion trillionaire. And not, you know, have a heat dome in Big Sur.

Jordan Thomas 36:21

There's an alternate universe in which we're not talking about this, because we acted on climate change early on and dodged that bullet. And then there's other problems that were that we're talking right now, but so basically it was, but there is this playbook that industries have used through time to really mix up science and confuse people. And so it goes back to the lead industry and the asbestos industry. The most recent one is the tobacco industry, which, you know the fact that cigarettes cause cancer was known for a very long time and then, but it took decades to get that approved because of this huge disinformation campaign. So the Koch brothers did was essentially just invest many, many, many, was it hundreds of millions or billions?between, between the Koch brothers, Exxon and this coalition of people who stood to not benefit from the transition to what all scientific and humanitarian and ethical reason was telling us to do communal there was billions of dollars that went into there's a really well coordinated campaign to confuse people about climate change, to fund politicians to try to unseat Republicans, and specifically Republicans who wanted to act on climate change and essentially to just dismantle the any sense of stable reason and understanding around this issue. And it really worked. You can see the you can see changes in Republican views of climate change just totally shift during this time to where it went from being a bipartisan issue to one that was extremely polarized, and then, since it was polarized, it was impossible to act on and that continues the day. So I think it's increasingly rare to encounter people who say that climate change isn't happening, but the effect is what matters. And if the effect is it maintains fossil fuel use and carbon emissions, then that's what matters. And so the rhetoric now is, climate change is happening, but it's not that bad. Or climate change is happening, but it's we're not going to feel the effects for a very long time, or the world's not going to end and or carbon capture is going to someday be get reach a point where we it'll save us. And so I think it's just like sticking to the basics, which is, what are the narratives that are maintaining the use of fossil fuels against all reason and at the expense of so many lives and so much economic data? And I think that that's what I'm trying to dig into in that chapter, specifically, while creating a juxtaposition of the air conditioned rooms in which these white men in their suits are making these decisions, right compared to the fire line, where it's 123 degrees and people are collapsing. And across the West Coast, hundreds of people, I think over 1000 people, died during that heat wave, which would have been virtually impossible if those decisions had not been made by those people in those air conditioned rooms.

Traci Thomas 39:29

Yeah, I want to talk about the heat, but I want to talk specifically about the heat as a firefighter, because you you explain it, and we don't have to go into deep detail, because it's explained quite well in the book. But when I started the book, literally, when I when I found out that I was going to be able to talk to you, my first question was, like, I mean, it's like, it's so hot and you're in the whole outfit, and it's hot in the outfit, just probably, like, even on a regular day when you're not around a fire. So how do you stay focused? How do you keep your body from cramping, like, all the sweating, all the losing weight? Like, logistically, how do you do it? And can you sleep at night? Like, I'm curious about the mental and physical health of these six month fire seasons. I know you talk about it in the book, but I could read seven books on just like, This is what I ate today. This is like, this is what my shower is. Like. Like, I just how day in and day out, are you, again, I'm just hot in my garage recording this podcast. You know what I mean. So like, how are you doing it? How are you and you have to be focused, because, you know, danger, danger, danger, fire.

Jordan Thomas 40:49

Yeah, so the interview to get on the Hot Shot crew is, formally, you sit down at a desk and they ask you all these questions and blah, blah, blah, it's just, it could be any corporate job or anything. But then you're in the woods, and you, the leader of the hot show crew asks you to go for a hike or to go for a walk, I'm sorry, to go for a walk. And if you want to get on the Hot Shot crew, you've talked to enough people to know that you need to have a 50 pound pack outside. And the walk is actually a race up to the top of this mountain, and what the leader of the Hot Shot crew is doing in the book I wrote, Aoki, it's different on some crews, but this is standard practice on a lot of them. He's asking you questions the whole time you're racing up the mountain, and you have to push yourself as hard as you can go, and you have to get up there fast. You have to, like, faster than a regular hiking speed for a hot shot crew, while maintaining conversation, because this is a test of your ability to be on that physical Brink while staying focused enough to talk and to be coherent. And what I was told on this for this crew was that when you get to the top, you have to look at him in the eyes, because he's going to be trying to tell whether you could then cut line for 13 hours, which is what, which means tunneling through brush with chainsaws. And so at the top of the mountain, he looks you in the eyes and tells you, great, this is how we get to work. And so I think the answer to that question is, how do you stay focused enough to stay safe is you have to go into the job with basically an Olympic level of athletic stamina

Traci Thomas 42:28

That doesn't even the heat of, like, that's just a hike on a day with a pack, but, like, it's, I mean, it's hot, near a fire, and you're wearing a lot of things to protect your body.

Jordan Thomas 42:41

You know, you would think that we'd be wearing a lot of things, but we're really not. You're in a pair of basically cargo pants that are fire resistant. You have a T shirt on underneath a relatively fire resistant shirt, and you have leather boots on. And that's it. That's it.

Traci Thomas 42:59

See, now I'm more scared. See, I'm now mentally, it's actually worse now, because I'm thinking, Oh, well, I'm really protected, but you're not even that protected. I just Jordan! How?

Jordan Thomas 43:09

So how you get you do get used to heat. You do get used to heat. The more you're in heat, the better you are at surviving it, to not collapsing in it.

Traci Thomas 43:21

Does it hurt your skin when you're so close to the heat?

Jordan Thomas 43:26

I mean, you get you again. You get kind of used to it. You're, I mean, it does, but you learn how to, like tilt your head so that it's blistering a hard hat instead of your skin. And so I'm just, I think it's one of the most brutal parts of the job, but it's also, I think, in a kind of weird, sick way, for a certain kind of person, it's one of the most alluring parts of it, because there is something so it's like such an intimate connection to your own body that you get when you are so attuned to your hydration based on the texture of your sweat, which you're just intuitively figuring out as you're working

Traci Thomas 44:09

How much water are you drinking a day? Are you drinkin like, Gatorade, or

Jordan Thomas 44:16

You carry six quarts with you, okay? Or like, six liters. And it's often not enough. You often need more than that, but it is just you learn to like, just exactly how much fuel you need. And you hear the same thing from stamina athletes who run like, 200 miles. Like, why would you ever do that? And people do it, I think because you enter this space of of understanding of your own body that is a hard to find outside of that. I mean, you could do yoga. That is another to do it.

Traci Thomas 44:47

I do yoga. I don't imagine that my yoga is the same. For some reason, I just I'm not seeing the connection I do yoga in my home. It's not very hot, you know. I love, I love a pigeon pose, but it's just, I don't know, I appreciate you saying it's the same, but I don't think it is.

Jordan Thomas 45:06

It is of, it is a matter of so I think I'm talking about, I've spoken a bit about the skills and the knowledge that it takes to be a wildland firefighter, and how we should be investing in this as a society, even if it was, even if it didn't take such technical skill, just the level of physical athleticism it takes to do this job alone makes it of its own form of expertise. So to train for the job, I rode my bicycle from San Diego to Cabo down Baja, because that's just like the best simulation you can get for the job, in a way, cycling for about eight hours a day through like 90 to 100 degree heat and sleeping on the ground and eating, just drinking water and eating,

Traci Thomas 45:55

I hate this. This sounds awful. I was such an indoor person. I'm just like, you couldn't do it. Eight hours on a bike. Oh my gosh. What about the mental health piece of it? I know you write about that, you know, you talk about your relationship, and sort of, you know, the impacts of that, and you have these, like, three days off, and the first two days you're sort of like coming down, and then the third day, it's like gearing up to go back out there. But what about after-after? What about now? Are you like? Is, do you have nightmares about this stuff? Did you ever? Do you feel like the impacts of sort of experiencing all of this are life altering mentally?

Jordan Thomas 46:45

So for me, again, I for a variety of reasons. I wasn't I was only I wasn't in the job for as long as many people were. And I can say, just from the time that I was in the job, it had when I was home, I'd have dreams that I was still cutting through brush on a chainsaw on the edge of the fire for because that's what you're doing for 13 hours a day, and then you go to sleep. It when the heat would get even when I was off, or in the winter, if the temperature went went over a certain amount of degrees outside, I'd have a extreme anxiety because of the heat stress that I've gotten in other situations, the sounds of two stroke engines like leaf blowers just spike adrenaline. This is a common experience, and it's one that's that's really hard for people, and it contributes to a lot of issues for people in the job, in terms of their own personal relationships, but their own but also you have high levels of substance abuse. You have really high suicidal tendencies. And again, this is it hasn't always been like this. This is a matter of just the planet changing faster than the the structure of the job does to where, well, people used to be fighting fires for like, you know, maybe a month out of the six month period. Now that's all you do. So you're just gone. It's like a military deployment where it hasn't always necessarily been like that. And there is discussion about this in the community now, when there hasn't been in the past. And there are structural alterations you can make to the job that would right, that would that would help with this. So for example, during the Biden administration, they gave us one extra day off between fires. So instead of two days off, we had three days off. There were people on the crew on the edge of tears by the relief of one extra day off. Wow. What other crews do? They have two crews. I mean, what other let's say, like for a county, for example, you could have two or three crews inhabiting one area so one crew can rest while the other one's out. That would be much more sustainable. That would just require a lot higher investment in our federal workforce on our public lands.

Traci Thomas 48:57

Yeah, okay, we have to do a hard shift because we're almost out of time. But I ask everyone this, how do you like to write? Where are you? how many hours a day? How often? snacks and beverages, music rituals? set the scene.

Jordan Thomas 49:14

You know, Traci I, I used to so I didn't really learn math in high school because I would just be scribbling stories in the back of class. Like stories used to be a compulsion for me.

Traci Thomas 49:25

I didn't learn math because I'm bad at math, but it's Thomas thing. Obviously, we are related.

Jordan Thomas 49:31

Maybe that's why I was writing. But this, this, this story, sort of felt like pulling teeth every single day. It was very difficult for me to get the words out. So I just got into a habit where I would try to wake up at 5am and go right until noon, and I would go to a space. I would read whatever sort of book I wanted to whose voice I wanted to emulate for like an hour, and then I would just force myself to just try to get material on the page. And I would focus on that, just getting things done onto the page. And I was, I think I probably listened to hermanos Gutierrez more than Well, I was in the .01% of Spotify listeners for this, for the Spanish guitar duo.

Traci Thomas 50:23

That's for Beyonce. I was really high up there. What writers were you reading to emulate, who were, who were some of your influences?

Jordan Thomas 50:31

I was all over the place. And I will say that was one of the huge joys of writing this book, was exposure to all of these different books. So in some of the chapters, it was different war correspondents like Luke Mogulson, who who spent a lot of time writing about, Well, during the during 2020, he wrote this beautiful book called The Storm, where he embedded with insurgents and right wing militias. But then in other ones, I was reading things like people like Haruki Murakami and the wind up bird chronicle to see how he shifts between people's experience in society, to dig deep into these subconscious levels of like of collective history and violence and kind of weaving through the surrealist narrative and the words that he uses to do this. So I went all over the place in my in the influences I was using.

Traci Thomas 51:22

And did you? Do you have any snacks and beverages when you write?

Jordan Thomas 51:27

way too much coffee, snacks? I would just try to eat a big breakfast

Traci Thomas 51:38

Boring! We love a snack around here. Okay, what about a word you can never spell correctly on the first try?

Jordan Thomas 51:43

Oh, gosh. There's so many words that I not only don't know how to spell but don't know how to pronounce rhythm, I never know how

Traci Thomas 51:52

Impossible! There's only one vowel and like 700 consonants.

Jordan Thomas 51:56

How many H's are in rhythm?

Traci Thomas 51:59

17, I don't know I couldn't tell you. Certainly couldn't tell you, is there anything that's not in the book that you wish could have been?

Jordan Thomas 52:09

Yeah, we got deployed to this super secret military site called area 18, which is where the United States detonated over 1000 nuclear bombs it was testing during the Cold War, and the fire was burning through this, this, this landscape, and there was a threat that would send a radioactive plume towards Las Vegas, and we had to go put it out. And I couldn't. I wrote that chapter like three times, they just couldn't get it all out, because it was because I think it's just hard for me to think about being in such a radioactive space and what's that gonna do. And that's just such a distillation of of the how people carry this job in their bodies, even after they leave the job, and just instills the need to, I think, have health care for everybody in society. But I wish I could have written about that. It just wasn't fitting, and I was having a hard time getting the words out. But it was so dystopian, so like, if you could imagine a climate apocalypse. It would look like this, a new a radioactive fire burning through a desert where the United States tested all of its nuclear bombs and now trains its special forces

Traci Thomas 53:32

that's your novel. That could be your novel when you're ready. That's definitely your novel.

Jordan Thomas 53:36

I do promise, though, the book's not all that grim, because there's so much levity in the community of people who I was working with, and the topic is, but there's also two second caveat is there is a lot of hope in space of fire, and there's a lot of levity and joy in the community of people, even those in such dire situations living on the edges of these disasters. There's some of the most laughter and some of the like, deepest sense of love and community that I've encountered anywhere in society, and it's on the edge of such such terrible events.

Traci Thomas 54:10

I feel like the human element, like your fellow your your comrades, your your friends, bring a lot of that to it, but I think the everything else is a little bleak, but there are moments of like, oh, like, I love that guy. Or, you know, there's like, this hike at the end. I don't, I won't spoil it, but there's a hike that you have with your friend, like, at the end, leading up to what would be your second, your second season. And that scene, I really was very like, I liked it a lot. It's very heartwarming.

Jordan Thomas 54:42

I was just gonna say, I think the things that are people are doing to try to prevent wildfires in California as well, those are just such promising spaces and people across California, the first Prescribed Burn Association in California, which is a group of people trying to bring back healthy kinds of fire. And. That was formed, I think, not that long ago, like a decade ago or something. And now there's prescribed burn associations popping up all over California, which is people coming together across differences, to talk about what their landscapes need and how they give land, their lands the kinds of fire they need. And that's not going to solve the wildfire crisis in general, but it'll it gives people a sense of place and hope and action and community, and it's I mean that, that that is where I encountered hope in the book, is people, yeah, acting and coming together and taking control of what they have power over in their immediate space. That doesn't, that doesn't negate the need to act politically at the federal level or at a large scale. But it is, it is an incredibly powerful movement, which, together, will hopefully make conditions much better for a lot more people across the state.

Traci Thomas 55:51

Yes, totally. 1,000% I have two more questions. One is for people who love this book when it all burns, what other books might you recommend that are in conversation with it?

Jordan Thomas 56:06

Oh, John Vaillant's book, Fire Weather is a really powerful example that focuses more directly on climate change. River Selby as well she was, she was a hot shot for many more years than I was, and offers just such a valuable perspective as a woman in the career that who has experiences that that I didn't and can provide so much insight that is, I think, really valuable when you're thinking about how to conceptualize these issues, and through conceptualizing them, how to try to act on them and solve them. So those are two that I would recommend to anybody.

Traci Thomas 56:49

I'm just going to recommend one of my favorite books about a fire, which is Paradise, about the paradise fire that I guess they're turning it into something. It's like a new movie or show or something.

Jordan Thomas 57:00

So I'll admit, when I was writing this book, I didn't read a single book about about fires because I was trying to, I didn't want to slip.

Traci Thomas 57:08

And that's what is really different. That book is like, about this fire. It's almost like, reads like a suspense novel, like it is the first scene is so intense, I was like, sick to my stomach reading it like, because it's just like, you're with the people as this fire is taking over the town, and it's a lot about, like, the municipal issues, and, you know, the exit routes and all of that. Like, it's a different kind of book about fire, but it really drives home the sort of civilian experience of being in a place that has one of these massive fires. And, like, what does that look like, what does that look like, and what does the recovery look like? And it's just like, Oh, it's so intense. Okay, my last question for you is, if you could have one person dead or alive read this book, who would you want it to be?

Jordan Thomas 57:55

I would say Aoki, since he was the crew leader, but he already read it.

Traci Thomas 58:00

What did he think?

Jordan Thomas 58:01

He said he liked it. Some of the other hot shots will probably make fun of him for it. I don't know. I don't know who I would like to read this book. I'm maybe Tom McClintock, the who's a congressman in California, and we were defending his watershed from a fire, while he was actively opposing increasing pay and healthcare benefits for wildland firefighters, on the premise, in his own words, the wildland firefighters are unskilled labor

Traci Thomas 58:37

So send him a copy. I'm gonna send one of my copies

Jordan Thomas 58:42

Maybe I would all of his constituents to read it, because he's because it's

Traci Thomas 58:47

like a community book club there,

Jordan Thomas 58:49

yeah, because he's up for reelection. And I think, I think it's if you're not looking after firefighters, like, Who are you looking after? And I think if we can hold politicians to that basic standard, then I mean, maybe it's optimistic. I think a lot of problems would be that would solve a lot of things.

Traci Thomas 59:06

I don't know. I feel like there's teachers all over who are like, what about us? I just feel like they're not looking after anybody. That's the point. How can we get rich? You could insert any. I mean, they're taking lunch away from kids. It's like, Who are you taking care of exactly, if not, all of these people who deserve to be taken care of anyways? Yeah.

Jordan Thomas 59:26

Well, firefighters are the focus of the story. But I think you could play Whack a Mole with like so many different professions, and see similar trends occurring in terms of being just seeing healthcare, not being adequate compensation not being adequate with conditions getting worse because of climate change and other and other issues. And it does seem like I was trying to capture a systemic trend in this that right hotshots are emblematic of, but not necessarily the only people occupying the space.

Traci Thomas 59:57

I think that's what makes the book so good. And. That it's so specific, like this one kind of firefighter in this one season, this one moment, right? But it's so indicative of all these other things, and it's connected to all these systemic issues, from, you know, access to healthcare, from climate change, mental health, like the politics, capitalism, the history, colonialism, like, it's tied to so many things. And I think that's what makes the book such an enraging, exciting, you know, entertaining and compelling read is because it's so narrow, right? It's not just like firefighters, it's specifically hot shots, right? And like, specific kind of forestry technician, but also it's connected to everything, and I think that's why it's easy to draw comparisons to teachers or, you know, nurses, or whatever you want it to be.

Jordan Thomas 1:00:53

I hope so.

Traci Thomas 1:00:54

With that being said, people in the world, you can go out and get when it all burns, it is there for you. I listen to some of it on audio. Jordan reads it. You do a great job. So I am giving it a gold star for both on the page and in the ear. Jordan, thank you so much for being here.

Jordan Thomas 1:01:12

Thanks for having me on Traci

Traci Thomas 1:01:14

And everyone else, we will see you in the stacks.

Alright y'all, that does it for us today. Thank you so much for listening, and thank you to Jordan Thomas for joining the show. I'd also like to say a huge thank you to Ashley garland and Shailyn Tavella for making this episode possible. Our book club pick for October is Frankenstein, and we will discuss that book on Wednesday, October 29 with Angela Flournoy as our guest. If you love the stacks, if you want inside access to it, head to patreon.com/thestacks to join The Stacks Pack and check out my newsletter at TraciThomas.substack.com make sure you're subscribed to the stacks Wherever you listen to your podcasts, and if you're listening through Apple podcasts or Spotify, please leave us a rating and a review for more from the stacks. You can follow us on social media at @thestackspod, on Instagram, threads and Tiktok, and now we are also on YouTube, and you can check out our website at thestackspodcast.com Today's episode of the stacks was edited by Christian Duenas, with production assistants from Wy'Kia Frelow and Sahara Clement. Our graphic designer is Robin McCreight, and our theme music is from Tagirijus. The Stacks is created and produced by me, Traci Thomas.